Next to a Volcano – Iceland, Russia, and a Red Line Declaration for the Council of Europe

“Why is it necessary to build such a system? Democracies do not become Nazi countries in one day. Evil progresses cunningly, with a minority operating, as it were to remove the levers of control. One by one, freedoms are suppressed, in one sphere after another. It is necessary to intervene before it is too late. A conscience must exist somewhere which will sound the alarm in the minds of a nation menaced by this progressive corruption, to warn them of the peril.”

Pierre-Henri Teitgen, former resistant, 1949

Dear friends,

Today, 16 May, the leaders of the 46 member states of the Council of Europe gather in Reykjavik, Iceland, for only the fourth Council of Europe Summit in history.

This could be a historic event. As the government of Iceland recalls:

“46 States with seven hundred million inhabitants are members of the Council of Europe. The aims of the Council are to protect human rights, democracy and the rule of law in Europe and improve the living standards of Europeans. The Council of Europe was founded in the aftermath of the Second World War to consolidate democratic stability, and thereby prevent the outbreak of another war in the continent.” (Government of Iceland, Reykjavik summit May 2023)

The last summit took place 18 years ago in Warsaw in May 2005. At the time, Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov declared that “Russia was, is and will be a great European nation. Today, no one must doubt Russia’s attachment to democracy and European values.”

This is the first Council of Europe summit since Russia was expelled from the organisation in early 2022. It is taking place against the background of Russia’s ongoing genocidal war against Ukraine, and shortly after the International Criminal Court has issued an arrest warrant for Russia’s president Vladimir Putin, “allegedly responsible for the war crime of unlawful deportation of population (children) and that of unlawful transfer of population (children) from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation.”

More than one year ago, the largest member state of the Council of Europe attacked a neighbour, bombed its cities, uprooted more than ten million of its people within a few months, and vowed to dismantle its state and destroy its national identity. This was a dark hour for Europe and the darkest hour in the history of the Council of Europe. As its leaders gather in the shadow of Iceland’s volcanos, they should draw lessons from their institution’s weak response to the many steps that led down the road to war.

Even before its massive military attack on Ukraine in February 2022, Putin’s Russia had attacked Georgia, another Council of Europe member state, in 2008. It had illegally annexed Crimea in 2014 and had waged a long and bloody war in Eastern Ukraine thereafter. It had carried out massive human rights violations in Chechnya and state-sponsored assassinations around the world. It had imprisoned and tortured political opponents, and then refused for years to implement the most important judgements of the European Court of Human Rights.

The Council of Europe was set up in 1949 to be a bulwark against the descent of any member state into fascism. With the European Convention on Human Rights as a reference point and with the European Court of Human Rights in Strasburg as a central institution, this oldest club of democracies is meant to sound an alarm in case of systematic human rights violations. It has failed to do so. This must not happen again. It is vital that member states recommit to defend the core principles on which the Council of Europe is based. And do so more vigorously than they have done in the recent past.

A red line declaration

It should be clear that, henceforth, violations of some of the core principles of the institution should lead to an immediate and strong reaction. Three such violations should be clearly identified: any military attack on another member; any systematic political imprisonment or torture, including the non-implementation of European Court of Human Rights judgements on these issues; and the reintroduction of the death penalty. Such violations should trigger an automatic and immediate reaction based on Article 8 of the Council of Europe’s statute:

- Any military attack on another member should lead to an immediate expulsion.

- Any systematic imprisonment of political prisoners or use of torture should lead to a suspension of voting rights in the Committee of Ministers.

- Any introduction of the death penalty should lead to expulsion.

ESI on Russia and the Council of Europe

- Expelling Oceania - The Council of Europe and Russian aggression (9 March 2022)

- Suspend Russia! The Council of Europe and the new cold war (23 February 2022)

- Human rights with teeth (I) – Battle of Europe (8 December 2018)

- Negotiating with a pointed gun – Sanctions, appeasement and the role of Russia in the Council of Europe (8 October 2018)

Russian attack on Georgia in 2008

Sounding the alarm

The Council of Europe was set up in 1949 to sound an alarm bell about the erosion of human rights in democracies. This reflected the conviction that governments violating the rights of their own citizens were also more likely to be aggressive towards their neighbours: to protect human rights across Europe was therefore also an issue of collective security.

This was certainly the experience of one of the spiritual fathers of the European Convention on Human Rights, French resistant fighter, later minister of justice, Pierre-Henri Teitgen. Teitgen played a key role drafting proposals for the European Convention on Human Rights. At the first ever session of the Council of Europe's assembly of parliamentarians in 1949 in Strasburg, Teitgen, who was a member, explained why a human rights court was needed to protect fundamental rights, following the tragic experiences of the first half of the 20th century:

“Europe should in fact be, first and foremost, the land of freedom. The history of our countries tells on every page the price she has had to pay for freedom in the past: nearly 20 centuries of suffering, of struggle, wars, revolutions: tears and blood shed without end … Finally, we won our freedom and our countries became as used to it as to the air they breathed - with the result that they did not perhaps esteem it highly enough. When the scourges of the modern world descended - Fascism, Hitlerism, Communism - they found us relaxed, sceptical and unarmed. We needed war, and for some of us, enemy occupation, to make us realise afresh the value of humanism.”

Teitgen saw the European Convention on Human rights, signed in Rome in 1950, as a bulwark against any renewed descent into fascism, a “conscience, of which we all have need.”

Piere-Henri Teitgen and David Maxwell-Fyfe

Teitgen’s co-rapporteur at the time, UK member of parliament David Maxwell Fyfe, a former British prosecutor at the Nurnberg trials, stated in August 1949:

“it is important to make clear the minimum standard consistent with membership of our body. This is the condition precedent to the general acceptance of the moral basis of our further activities.”

At Reykjavik, member states should recall this moral basis and reaffirm their determination to defend the minimum standards for membership. On Russia, the Council of Europe’s institutions and the member states represented in the Committee of Ministers failed to react until it was too late.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sergei Magnitski |

Alexey Navalny |

Anna Politkovskaya |

Vladimir Kara-Murza |

Natalya Estemirova |

Sergei Magnitzky – murdered in prison for exposing corruption.

Alexey Navalny – imprisoned, subject to poison attack on his life.

Anna Politkovskaya – murdered for exposing human rights violations.

Vladimir Kara-Murza – imprisoned, subject to poison attacks on his life.

Natalya Estemirova – murdered for exposing human rights violations.

The road to Iceland

In October 2022, a High-Level Reflection Group of the Council of Europe published a report in the run up to the Iceland summit. The Group noted that the institution had to adapt:

“The Russian Federation’s aggression against Ukraine constitutes a blatant violation of the Council of Europe’s Statute and led to the Russian Federation’s expulsion from the Organisation … the Council of Europe – the continent’s main pan-European organisation – must adapt in order to remain fit for purpose.”

It added:

“Our democracies are not established once and for all. We need to strive to uphold them each and every day, continuously, in all parts of our continent, at all levels of government, and guard against authoritarian leaders and democratic backsliding. Democracy is not just about what happens on election day. True democracies require that elections be free and fair, that opposition candidates may present themselves without fear of arrest or being silenced by other means.”

However, the report did not dwell on the most troubling lesson from the more than two decades of Russia’s membership: the absence of any strong reaction by other member states in advance of the full-scale assault on Ukraine in 2022, which then made Russia’s expulsion inevitable. An earlier reaction might have made an impact. It would certainly have shaken European complacency and reflected the letter and spirit of its Statute.

Article 3 of the Statute of the Council of Europe refers to the fundamental freedoms and the key notion of sincere collaboration in their realisation:

“Every member of the Council of Europe must accept the principles of the rule of law and of the enjoyment by all persons within its jurisdiction of human rights and fundamental freedoms, and collaborate sincerely and effectively in the realisation of the aim of the Council as specified in Chapter I.”

Article 8 of the Statute spells out the consequences of continuous serious violation of these core principles:

“Any member of the Council of Europe which has seriously violated Article 3 may be suspended from its rights of representation and requested by the Committee of Ministers to withdraw under Article 7. If such member does not comply with this request, the Committee may decide that it has ceased to be a member of the Council as from such date as the Committee may determine.”

The Council of Europe has the tools to react to serious violations. It can defend its values. The question is whether its member states have the will to do so before expulsion becomes the only option.

The centrality of political prisoners

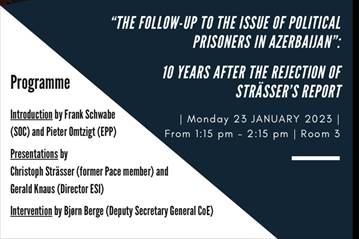

Earlier this year, in January 2023, two prominent members of PACE, Frank Schwabe and Pieter Omtzigt, hosted a debate on lessons from another historic failure of the Council of Europe, related to the issue of political prisoners.

The occasion was the 10th anniversary of the PACE debate on political prisoners in Azerbaijan on 23 January 2013. The vote back then was historic: a resolution on political prisoners by a German PACE rapporteur was defeated by 125 votes against 79 votes, with 20 abstentions, sending a strong signal of support to the authoritarian regime in Baku. This was followed by a wave of new arrests.

Video of 2023 Political Prisoners and corruption debate in Strasburg

In their presentations, speakers recalled this scandal and discussed lessons and proposals: how to apply the definition of political prisoner adopted at the time to ensure that there will never again be political prisoners in any Council of Europe member state.

For this, the 2012 Council of Europe definition of political prisoners remains as useful and relevant as ever.

A person deprived of their personal liberty is to be regarded as a ‘political prisoner’:

a. if the detention has been imposed in violation of one of the fundamental guarantees set out in the European Convention on Human Rights and its Protocols, in particular freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of expression and information, freedom of assembly and association;

b. if the detention has been imposed for purely political reasons without connection to any offence;

c. if, for political motives, the length of the detention or its conditions are clearly out of proportion to the offence the person has been found guilty of or is suspected of;

d. if, for political motives, he or she is detained in a discriminatory manner as compared to other persons; or,

e. if the detention is the result of proceedings which were clearly unfair and this appears to be connected with political motives of the authorities.

Will the 2023 Iceland summit bring the vision of a more robust Council of Europe closer?

Will there be a clear message on core principles, and on the renewed determination of member states to defend these in the future?

Certainly, no member state of the Council of Europe should be able to get away with imprisoning politicians, journalists and human rights defenders on false grounds, or to ignore judgements on such arrests by the European Court of Human Rights. From now on, this must have consequences. Let this be the signal and message from Iceland.

Yours sincerely,

Gerald Knaus

The European Stability Initiative is being supported by Stiftung Mercator

Towards a Europe without political prisoners – Strasburg January 2023

Pieter Omtzigt, Gerald, Frank Schwabe

- ESI proposal: Caviar Diplomacy – Why every European should care

- "The Aserbaidschan Connection" debate with Frank Schwabe, Lobby Control, and Transparency International, 26 July 2021

- ESI newsletter: The strangest love affair – autocrats and parliamentarians, from Berlin to Strasbourg, 2 April 2021

- FAZ, Eine allgemeine Atmosphäre der Käuflichkeit ("A general atmosphere of venality"), 30 March 2021

- ESI: Azerbaijan debacle: The PACE debate on 23 January 2013

- ESI: Showdown in Strasbourg - The political prisoner debate in October 2012

Knut Abraham, MP in the Bundestag

VIDEO:

Presentation on Reykjavik summit, red lines and the Council of Europe

(English subtitles)

Osman Kavala, in jail in Türkiye since 2017

On 11 July 2022, the European Court of Human Rights stated in a ruling on Osman Kavala:

“The whole structure of the Convention rests on the general assumption that public authorities in the member States act in good faith …

… It is clear from the verdict delivered on 25 April 2022 that this conviction was based on facts primarily related to the Gezi Park events, which the Court had scrutinised with particular care in its initial judgment on account of the clear absence of reasonable suspicion …

In the light of the conclusions it has set out above, the Court considers that the measures indicated by Türkiye do not permit it to conclude that the State Party acted in “good faith”, in a manner compatible with the “conclusions and spirit” of the Kavala judgment, or in a way that would make practical and effective the protection of the Convention rights which the Court found to have been violated in that judgment.”

At its March 2023 meeting, the Committee of Ministers adopted the following decision:

“recalled the Court’s findings in the Kavala v. Turkey judgment of 10 December 2019, that the applicant’s arrest and pre-trial detention took place in the absence of evidence to support a reasonable suspicion he had committed an offence (violation of Article 5, paragraph 1, of the Convention) and pursued an ulterior purpose, namely to silence him and dissuade other human rights defenders …

… deeply deplored that Mr Kavala remains in detention;

… recalling the shared responsibility of all competent authorities, including the judiciary, to achieve restitutio in integrum, and that the judicial instances are capable of putting an immediate end to the applicant’s detention, urged the competent Turkish authorities to ensure that all the negative consequences of the criminal charges brought against the applicant are eliminated without further delay, in particular by ensuring that he is immediately released.”

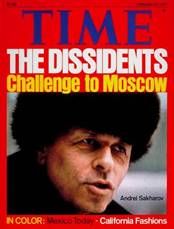

“On the moral plane the persecution of persons who have defended other victims of unjust treatment, who have worked to publish and in particular to distribute information regarding the persecution and trials of persons with deviant opinions, and of conditions in places of internment, is particularly important.” Andrei Sakharov, accepting the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975

Andrei Sakharov and the defence of the unjustly persecuted - 23 September 2014

ESI newsletter, 2014 and the threat to Sakharov's legacy

ESI conference - "For a Europe without political prisoners" - 2 June 2014

“Europe without political prisoners” Suggestions for Concrete Steps, 2014

Update: advocacy campaign for a Europe without political prisoners, 2014