Breaking a deadlock – the genius of Ahtisaari – a peace formula

- A substantial and tangible step – 15 May 2024

- The wisdom of Ahtisaari

- The Ahtisaari formula

- A peace strategy

- Why Council of Europe accession matters

Dear friends of ESI,

The policy of European democracies towards Kosovo is reaching a turning point, as 46 European governments decide on Kosovo’s application to the Council of Europe. At stake is the survival of the strategy of peace building in the Balkans developed by a previous generation of European diplomats, including the late Martti Ahtisaari. That strategy was based on the idea that the respect of human rights, objectively assessed, would hasten Kosovo’s integration into European institutions, making future conflict in the region less likely. And that Serbia would have no veto in this process.

In April 2024, following four reports (by Eminent Lawyers and in three committees in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe – PACE) and four votes in favour of Kosovo’s accession, PACE recommended that Kosovo joins the organisation. Former Greek foreign minister Dora Bakoyannis summed up the findings by PACE:

“To reach a positive Opinion, it took 300 days, missions to Pristina, North Mitrovica and Brussels, a team of specialized lawyers, and dozens of meetings with governments, ambassadors, Serbian mayors, representatives of the Serbian Orthodox Church, NGOs, and international organizations.

It also required the authorities in Pristina to restore, after 25 years, the property of the most important Serbian Monastery in the region, to retract a bill for the express expropriation of Serbian properties, and to sign a long list of human rights agreements that, above all, put the Serbian minority under international protection.

No candidate member has ever been asked to undertake so many reforms before even being brought up for discussion on its accession to the Organization. This is probably why 83% of the Assembly voted in favor of the Report.”

Article by Dora Bakoyannis, 1 May 2024

The verdict of PACE could not have been clearer: Kosovo met the conditions to join the organisation. And yet, some argued immediately that Kosovo had still not done enough and that the PACE recommendation should be ignored. Already in March 2024, US envoy Gabriel Escobar stated that for membership in the Council of Europe, Kosovo must first “establish the Association of municipalities [ASM] with a Serbian majority”, a condition not raised by PACE.

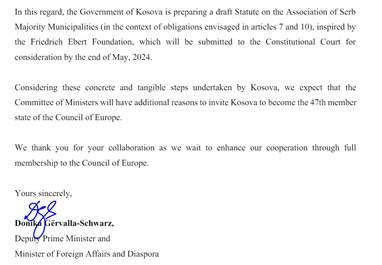

Donika Gervalla-Schwarz

A substantial and tangible step – 15 May 2024

On 22 March 2024, in the list of post-accession commitments sent to PACE by Kosovo’s three leaders, these committed themselves to “take substantial and tangible steps with a view to implementing all articles of the Brussels and of the Ohrid Agreements which includes establishing the Association of Serb majority municipalities as soon as possible.”

A breakthrough proposal – 15 May 2024

Yesterday, 15 May 2024, Kosovo’s government has taken such a decisive step. In a letter to PACE President Rousopoulos, Kosovo Deputy prime minister and foreign minister Donika Gervalla-Schwarz explained:

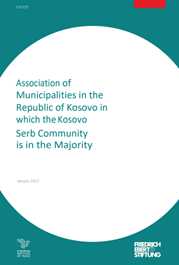

“We have already started consultations with representatives of the members of the Serb community to take note of the needs of municipal service-based cooperation and association. In this regard, the Government of Kosova is preparing a draft Statute on the Association of Serb Majority Municipalities (in the context of obligations envisaged in articles 7 and 10), inspired by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation draft proposal, which will be submitted to the Constitutional Court for consideration before the end of May, 2024.

Considering these concrete and tangible steps undertaken by Kosova, we expect that the Committee of Ministers will have additional reasons to invite Kosova to become the 47th member state of the Council of Europe.”

This creates a huge opportunity to resolve an issue that has been left unresolved since 2013, in line with Council of Europe standards. It should also open the door to Kosovo joining the Council of Europe, if not this week, then at an extraordinary Committee of Ministers meeting within a few weeks this summer.

The wisdom of Ahtisaari

This letter offers the international community – including all European democracies – a way to get Kosovo policy back on track by remembering the insights of one of Europe’s great diplomats, Martti Ahtisaari.

Martti Ahtisaari, a child refugee, fleeing his native Karelia following Stalin’s war of aggression, worked on resolving conflicts from Namibia to Northern Ireland, from Indonesia to the Balkans. In 1999, as President of Finland, he facilitated the withdrawal of Serbian military forces from Kosovo, ending the war. In November 2005, Ahtisaari returned to the Balkans as Special Envoy of the UN Secretary-General for the status process for Kosovo and submitted a masterpiece of international diplomacy in February 2007. The Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement or, in short, the Ahtisaari Plan, has inspired Kosovo’s constitution and its minority protection system until today.

Ahtisaari’s vision for a stable peace in the Balkans was based on three key ideas:

1. Realism on the Kosovo status issue: acknowledging that Serbia will not recognise Kosovo any time soon.

2. The proposal of a Grand Bargain that is not dependent on Serbia recognising Kosovo, linking the protection of human and minority rights inside Kosovo with Kosovo’s integration into the community of democratic states as an equal partner.

3. The vision of a realistic European future for both Kosovo and Serbia. Kosovo’s integration into the international and especially European system would “make another war unthinkable” before long.

A good diplomat is always a realist. This means accepting that sometimes even the most accomplished mediator cannot help two parties reach a certain agreement. When, in March 2007, Ahtisaari submitted his report as Special Envoy on Kosovo’s future status, he concluded, following long, intense negotiations:

“it has become clear to me that the parties [Serbia and Kosovo] are not able to reach an agreement on Kosovo’s future status … It is my firm view that the negotiations’ potential to produce any mutually agreeable outcome on Kosovo’s status is exhausted. No amount of additional talks, whatever the format, will overcome this impasse.”

In 2007, the Serbian president was Boris Tadic, the prime minister Vojislav Kostunica. Today, the Serbian president is Aleksandar Vucic, the (new) prime minister Milos Vucevic. But on the issue of Serbian opposition to Kosovo independence nothing has changed or will change any time soon.

Ahtisaari accepted this reality. He then drew the right conclusion. Peace needed to be assured without Serbian recognition. Serbia could not have a veto on Kosovo’s progress. His proposal was a Grand Bargain between Kosovo and other democracies: Kosovo would declare its independence on the basis of a commitment to the highest standards of human rights and minority protection; in return, its statehood would be recognised by others, starting with Western democracies. The formula of his Grand Bargain was simple:

A guarantee of minority and human rights inside Kosovo to ensure domestic peace.

Recognitions of Kosovo statehood by other states to consolidate regional peace.

Kosovo’s leaders embraced this formula. On 17 February 2008, 109 members of the Kosovo parliament declared:

“We, the democratically elected leaders of our people, hereby declare Kosovo to be an independent and sovereign state. This declaration reflects the will of our people and it is in full accordance with the recommendations of UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari and his Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement …”

Kosovo could not compel Serbia to recognise its independence. There was nothing its leaders could offer Serbia to change its mind on its status. However, Kosovo’s leaders could convince other states to back its integration into the international system of democracies by adherence to the human rights-based formula proposed by Ahtisaari.

It is vital that key European democracies do not turn their back on Ahtisaari’s insights. It is unrealistic to believe, against all evidence, that Serbia might be persuaded to recognize Kosovo’s status soon, if only Kosovo can be pressured to make concessions to Serbia. And it would be going against Ahtisaari’s core idea to make Kosovo’s integration into institutions such as the Council of Europe dependent on Serbian approval, an approval that will certainly be withheld.

Master diplomat

The Ahtisaari formula

Ahtisaari’s recommendations on minority rights were developed with input from the leading experts and institutions in Europe. They were enshrined in the constitution and in legislation shortly after independence. They are amongst the most extensive in the world.

Ahtisaari’s vision was also that of a political system based on powerful municipalities with exclusive rights, including the right to create partnerships and associations, that cannot be taken away by the central government, enshrined in the constitution and in laws on decentralisation or municipal partnerships. This, according to Ahtisaari, was to focus:

“… on the specific needs and concerns of the Kosovo Serb community, which shall have a high degree of control over its own affairs. The decentralization elements include, among other things: enhanced municipal competencies for Kosovo Serb majority municipalities …; extensive municipal autonomy in financial matters, including the ability to receive transparent funding from Serbia; provisions on inter-municipal partnerships and cross-border cooperation with Serbian institutions; and the establishment of six new or significantly expanded Kosovo Serb majority municipalities.”

The following is a non-exhaustive list of the rights that the Serb community and Serb-majority municipalities already possess today. All these rights are not something to be attained in the future: they are what Kosovo’s constitution and laws guarantee today.

Members of the Serb Community have the right to:

“Receive public education in one of the official languages of Kosovo of their choice at all levels; Establish and manage their own private educational and training establishments for which public financial assistance may be granted.”

All Kosovo municipalities have extensive full and exclusive competencies for:

“a. Local economic development;

b. Urban and rural planning;

c. Land use and development;

d. implementation of building regulations and building control standards;

e. Local environmental protection;

f. Provision and maintenance of public services and utilities, including water supply, sewers and drains, sewage treatment, waste management, local roads, transport and heating schemes;

g. Local emergency response;

h. Provision of public pre-primary, primary and secondary education, including registration and licensing of educational institutions, recruitment, payment of salaries and training of education instructors and administrators;

i. Provision of public primary health care:

j. Provision of social welfare services, such as care for the vulnerable, foster care, child care, elderly care, including registration and licensing of these care centers, recruitment, payment of salaries and training of social welfare professionals;

k. Public housing;

1. Public health;

m. Licensing of local services and facilities, including entertainment, cultural and leisure activities, food, lodging, markets, street vendors, local public transportation and taxis;

n. Naming of roads, streets and other public places;

o. Provision and maintenance of public parks and spaces;

p. Tourism;

q. Cultural and leisure activities;

r. Any matter not explicitly excluded from their competence nor assigned to any other authority.”

Serb-majority municipalities in Kosovo have their own competencies further enhanced:

“The municipality of Mitrovica North shall have competence for higher education, including registration and licensing of educational institutions, recruitment, payment of salaries and training of education instructors and administrators.

The university of Mitrovica North shall be an autonomous institution of higher learning. The municipality of Mitrovica North shall have authority to exercise responsibility for this public Serbian language university. The municipality of Mitrovica North may cooperate with any other municipality in operating the university.

The municipalities of Mitrovica North, Gracanica, Strpce shall have competence for provision of secondary health care, including registration and licensing of health care institutions, recruitment, payment of salaries and training of health care personnel and administrators;”

All Serb-majority municipalities in Kosovo also have:

“Authority to exercise responsibility for cultural affairs, including protection and promotion of Serbian and other religious and cultural heritage within the municipal territory, as well as support for local religious communities;

Enhanced participatory rights in the appointment of Police Station Commanders;

Schools that teach in the Serbian language may apply curricula or textbooks developed by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Serbia upon notification to the Kosovo Ministry of Education, Science and Technology.”

All municipalities, including the ten Serb-majority municipalities, also have:

“The right to inter-municipal and cross-border cooperation in the areas of their own and enhanced competencies. Municipalities exercising enhanced municipal competencies may cooperate with any other municipality in providing such services.

Based upon the principles of the European Charter of Local Self-Government, municipalities shall be entitled to cooperate and form partnerships with other Kosovo municipalities to carry out functions of mutual interest, in accordance with the law.

Municipal responsibilities in the areas of their own and enhanced competencies may be exercised through municipal partnerships, with the exception of the exercise of fundamental municipal authorities, such as election of municipal organs and appointment of officials, budgeting, and the adoption of regulatory acts enforceable on citizens in general;

Municipal partnerships may take all actions necessary to implement and exercise their functional cooperation through, inter alia, the establishment of a decision making body comprised of representatives appointed by the assemblies of the participating municipalities, the hiring and dismissal of administrative and advisory personnel, and decisions on funding and other operational needs of the partnership;

Based upon the principles of the European Charter of Local Self-Government, municipalities shall be entitled to form an association of Kosovo municipalities for the protection and promotion of their common interests, in accordance with the law. Membership in such associations shall be limited to Kosovo municipalities. Such associations may cooperate with their international counterparts. Such associations may offer to its members a number of services, including training, capacity building, technical assistance, research related to municipal competencies and policy recommendations.

Municipalities shall be entitled to cooperate, within the areas of their own competencies, with municipalities and institutions, including government agencies, in the Republic of Serbia. Such cooperation may take the form of the provision by Serbian institutions of financial and technical assistance, including expert personnel and equipment, in the implementation of municipal competencies.

Municipalities shall be entitled to receive financial assistance from the Republic of Serbia. Any financial assistance to Kosovo municipalities from the Republic of Serbia shall be transparent and made public. Municipalities may receive financial assistance from the Republic of Serbia through accounts in commercial banks, certified by the Central Banking Authority of Kosovo. Any receipts shall be notified to the Central Treasury.

Financial assistance from the Republic of Serbia to Kosovo municipalities shall not offset the allocation of grants and other resources provided to municipalities and shall not be subject to taxes, fees or surcharges of any kind imposed by any central authority.

Individualized transfers, including pensions, to individual Kosovo citizens may be effected with funding from the Republic of Serbia.”

This, then, was the Grand Bargain offered in 2007. And, as the Council of Europe found in its assessment and vote this year, Kosovo has delivered on its side of the bargain. Even if not all of these rights have been exercised: for instance, Serb-majority municipalities have not yet chosen to create the association or municipal partnerships which they have the right to create. However, most provisions – from Serbian-language education to tertiary health care funded in part by Serbia to extensive municipal competencies – are being applied.

What is striking: Today some seem to have forgotten that all this already exists! And that this was the basis on which so many democracies recognised an independent Kosovo in 2008, promising it integration into the European system of states in return for building a state on these principles.

A peace strategy

Serbia was never impressed by the high level of protection for Kosovo Serbs set out in Ahtisaari’s Plan. It was not swayed by any constitutional arrangement, however inventive, to recognise Kosovo’s independence.

But what was really expected from Serbia under this Ahtisaari formula? This leads us to Ahtisaari’s third key insight: what is required for peace to be kept is simply for Serbia to give up the hope that it might ever again recover control over Kosovo by force. This is achieved, in part, by maintaining international peace-keepers in Kosovo, but mostly by integrating Kosovo into the international system as an equal.

For the foreseeable future, Serbia’s position on Kosovo might resemble that of governments in Ireland, in the decades when the 1937 Irish Constitution laid claim to territory of Ireland’s neighbour, the United Kingdom, in Northern Ireland:

Article 2

The national territory consists of the whole island of Ireland, its islands, and the territorial seas.

Article 3

Pending the re-integration of the national territory, and without prejudice to the right of the parliament and government established by this constitution to exercise jurisdiction over the whole territory, the laws enacted by the parliament shall have the like areas and extent of application as the laws of Saorstát Éireann [Irish Free State] and the like extra-territorial effect.

The 1937 Irish Constitution distinguished between the “national territory” and the “extent of application” of Irish laws. It asserted the right of the Irish parliament and government to “exercise jurisdiction over the whole territory” at their discretion. This was a territorial claim for control of Northern Ireland, which remained in place for over 60 years.

The Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985 – six decades after independence

However, when Ireland and the UK joined the Council of Europe and, in 1973, the European Economic Community, both countries became members of the same international organisations. Over time, as they confronted each other as equal partners in these institutions, relations between Dublin and London improved. Societies left behind bitter memories, including those of the Irish war of independence. The process of EU integration and finally the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland in 1998 helped to make the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland invisible. In 1999 the territorial claim in the Irish constitution was revoked following a referendum.

![]()

The Belfast Agreement of 1998 – another decade later

“Building trust over time” through cooperation and integration was a familiar formula for Ahtisaari. In July 1999, Ahtisaari also chaired the Sarajevo Summit where, immediately after the end of the Kosovo war, a Sarajevo Declaration offered all interested Western Balkan states a European peace formula:

“From Sarajevo, we affirm … our shared responsibility to build a Europe that is at long last undivided, democratic and at peace. We will work together to promote the integration of South Eastern Europe into a continent where borders remain inviolable but no longer denote division and offer the opportunity of contact and cooperation.”

1999 victims in Kosovo

The goal in Sarajevo was to make “war unthinkable” by changing the nature of borders and societies through integration and cooperation. Borders were to become both inviolable and invisible.

CNN on the Sarajevo summit, July 1999

This project was also pursued at the historic Helsinki EU summit in December 1999, again chaired by Ahtisaari, which opened the door to the 2004 Big Bang enlargement that would transform the continent. This turned the Western Balkans into an island surrounded by the EU.

Why Council of Europe accession matters

In response to the 15 May 2024 letter by the Kosovo government on the ASM to the Council of Europe, Serbian president Aleksandar Vucic declared:

“This is another trick that Albin Kurti and his helpers, including Gerald Knaus and all their other lobbyists, are carrying out together. They themselves say that they will submit their text by the end of May. And who are you to submit your text? In the Brussels Agreement, it is quite clear that this should be done by the management of Serbia, or if we agree, as we agreed contextually, conceptually and in principle, that it should be the text submitted by the EU - what do they have to do with it and what do they have to deliver anything. Of course, this is a trick because the English are now pressuring everyone else to accept Kosovo's membership in the Council of Europe …”

In other words, according to the Serbian president, Kosovo is not to submit any draft statute of the ASM to its Constitutional Court even if it meets all Council of Europe standards (and all the expectations ever expressed by the international community in respect of it – see Annex below) , before it can join the Council of Europe, unless it is agreed with Serbia first. This is a trap: for Kosovo, but also for the international community.

For Serbian leaders assert that Kosovo must never join the Council of Europe. This month, incoming prime minister Milos Vucevic warned that Serbia will always, under any circumstances, oppose Kosovo joining the Council of Europe:

“The so-called Kosovo is not and will never be a state, and therefore, according to the rules of the Council of Europe, it cannot be admitted to the membership of that organization.”

Vucevic announced that “the biggest challenge in the upcoming period for the new [Serbian] government will be defending the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the country [Serbia, including Kosovo].“ This turns the ASM issue into a convenient tool to stop Kosovo. And to overturn the Ahtisaari formula.

What is currently at stake in the debate on Kosovo accession to the Council of Europe is the survival of this formula, which held that as Kosovo fulfils its human rights and minority rights obligations, enshrined in its constitution and laws, it will be supported by all the countries which recognised it on its path to join European institutions. And that, while Serbia could not be forced to recognise Kosovo, it would not be able to veto Kosovo’s integration into European institutions.

European democracies must make clear that this vision is still alive. The moment to prove this is now, the institution where to do so is the Council of Europe. As the Kosovo government has offered a constructive proposal to address the long unresolved issue of an ASM, in line with Council of Europe standards, European democracies need to hold to their side of the bargain.

On the other hand, by insisting on conditions that would give Serbia a veto and which are not linked to the Council of Europe, European leaders would renege on the Ahtisaari formula. They would block Kosovo not on merit, but arbitrarily. They would signal to Serbia that things settled in 2008 are now up for renegotiation. This would be an invitation to more threats, risking more violence as in autumn 2023, and the end of the stability which Ahtisaari brought.

The best way to prevent this is to admit Kosovo as 47th member of the Council of Europe as soon as possible. Tomorrow, foreign ministers in Strasbourg should set a new date for an extraordinary meeting within a few weeks, to be able to vote on Kosovo’s application once it has moved forward on the issue of the ASM. This would send a clear signal to Serbia that Kosovo’s statehood is here to stay, and retains the full backing of European democracies.

Martti Ahtisaari would certainly have been very pleased to see Kosovo join the Council of Europe this year.

Yours sincerely,

Gerald Knaus

More on Kosovo’s accession process to the Council of Europe:

May 2022: ESI newsletter: 47 again? Russia out, Kosovo in, 16 May 2022

March 2024: ESI newsletter and report: A monastery, Kosovo courts and the road to the Council of Europe

April 2024: Historic vote – Kosovo’s breakthrough – a Unicorn

ANNEX A – The ASM saga

In every European democracy, also in the Balkans, associations of municipalities are created by municipalities. In any country with strong minority protections and many exclusive rights of (minority and other) municipalities, the idea that a central government might IMPOSE by decree statutes of an association of municipalities on minority municipalities, statutes that these did not themselves vote for, would constitute a serious violation of Council of Europe standards values. Kosovo’s government cannot unilaterally “establish” the Association without violating its constitution, against the will of elected Kosovo Serb mayors.

However, Kosovo governments have committed to support the process of establishing an ASM. They said so in 2013, in 2023, and in a letter to PACE in March 2024:

In April 2013, in an Agreement reached in Brussels between Kosovo and Serbia and ratified by the Kosovo parliament in June that year, both (!) parties committed to a goal: “There will be an Association/Community of Serb majority municipalities in Kosovo.“ And: “The structures of the Association/Community will be established on the same basis as the existing statute of the Association of Kosovo municipalities …”

In August 2015, EU High Representative Federica Mogherini wrote a letter to explain how the European Union understood the ASM mentioned in the 2013 First Agreement: it “will not have executive powers.”

In December 2015, the Kosovo Constitutional Court issued a judgement on the ASM, referring to Article 12 of the Kosovo Constitution, which defines municipalities as “the basic territorial unit of local self-governance in the Republic of Kosovo”: “the legal act and the Statute of the Association/Community shall not replace or undermine the status of the participating municipalities as the basic units of democratic local self-government within the meaning of Article 12 and Chapter X of the Constitution.”

In January 2023, a US State Department adviser and US Envoy Gabriel Escobar, himself wrote about the ASM: “What the Community would not be? It would not add a new level of executive and legislative power to the Government of Kosovo. This important principle dates back to Ahtisaari’s proposal. Municipalities cooperate in the joint management of jurisdictions within the framework of legitimate Kosovo institutions and structures. Allowing certain municipalities to more effectively exercise the powers they already have.”

In February/March 2023, in the so-called Ohrid Agreement, the words Association or Community of Serb-majority municipalities do not appear. Again, both (!) parties committed themselves to “ensure an appropriate level of self-management for the Serbian community in Kosovo and ability for service provision in specific areas, including the possibility for financial support by Serbia.”

What follows from this? Any ASM has to respect the Kosovo constitution, protect the rights of municipalities, not create a new layer of government, and not transfer executive authorities away from municipalities. Any ASM that meets these conditions would be legitimate.

ANNEX B – What is wrong with the Lajcak ASM proposal?

In October 2023 the Quint (US, Germany, France, UK, and Italy) proposed a version of an ASM statute. This document has no official author. The official Serbian reaction in May has been that this is not acceptable as it stands but at best a “good basis for continuing discussions.” So far, no elected Kosovo Serb major has endorsed this statute either. It is not clear what purpose is served pressuring the Kosovo government to adopt and then send a draft to its Constitutional Court which nobody concerned – above all the municipalities to be associated - agrees to.

In addition, there are two problems with the draft. First, the draft says that any dispute between the ASM and the Kosovo central authorities regarding the application and interpretation of the statute can be submitted permanently by either party to an arbitration commission, with the chair appointed by the EU in case of disagreement. Even in the phase of supervised independence after 2008, international mechanisms were designed in a way to be phased out. This one would be a permanent feature:

“The arbitration commission shall be composed of one arbitrator to be nominated by each party to the dispute, and another arbitrator to be appointed as chairperson of the commission upon consensus of the parties to the dispute.

If, within three months, either party to the dispute fails to nominate the respective arbitrator or the parties to the dispute fail to agree on the appointment of the chairperson, this arbitrator or chairperson shall, at the request of either party to the dispute, be appointed by the European Union.”

At the same time, Kosovo municipalities, where real executive power rests and which are recognized in the Kosovo constitution, would rely on the Kosovo judicial system in any disputes – like everyone else in Kosovo. The same would be true for every other association in Kosovo.

Second, the proposed provisions on education and health care are unworkable. The proposal stipulates that a ‘Kosovo Serb Education Network’ and a ‘Kosovo Serb Healthcare Network’ shall be established as private education and healthcare providers, managed by the association. It states that “in the territory of the members of the Association, these providers may use the public premises established and co-funded by Serbia for the provision of health and education services,” and that “the operation of these networks shall in no way limit or hinder the functioning of the existing Kosovo system of public schools and the Kosovo system of public healthcare.” While Serbia would be financing these networks and the “main offices of these providers [would be] currently located in Serbia”, the networks would be licenced in Kosovo in accordance with applicable law.

Kosovo’s constitution guarantees the Serb community “public education in one of the official languages of the Republic of Kosovo of their choice at all levels” (Article 59 in the Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo). A fully private network would fall short of this right. Currently, schools and health care buildings in Serb municipalities receive funding from both the Serbian and the Kosovar budget. How could the ASM use existing health care buildings and not hinder the functioning of the Kosovo public system?

ANNEX C - What is in the gist of the FES–EIP proposal?

In January 2023, the German Friedrich Ebert Stiftung and the European Institute of Peace published a proposal for a draft statute for an ASM. Its central point is its article 4:

“In the fulfilment of its objectives, the Association/Community will not undermine or circumvent the constitutionally and legally provided authority and competences of the participating municipalities nor in any way replace or undermine the constitutionally and legally provided relationship between the central and local authorities in the Republic of Kosovo.” (art. 4)

The key points of this proposal are that:

- membership in the association is voluntary. “The activities of the Association/Community are based on the principles of voluntary participation by its members ...”

- it will “exercise full overview” over several areas, most importantly “to develop local economy”, “in the area of rural and urban planning”, “in the area of education” and “to improve local primary and secondary health and social care”. The activities listed in the proposal make clear that this does not mean the exercise of executive functions. The activities listed include:

“Facilitating cooperation”

“Representing policy interests”

“Conducting research”

“Providing legal, scientific, financial and secretarial support to its members”

“Providing advice to the central authorities”

“Funding scholarships, teacher training, research grants, IT solutions, academic exchanges, summer programmes, and other”

“Funding construction and infrastructure projects related to the provision of education”

“Funding and facilitating capacity building and professional training of medical and social welfare personnel”

“Funding construction and infrastructure projects related to the provision of health care and social welfare”

“Funding the facilities, equipment and material expenses related to any specific health or social welfare needs in the participating municipalities” (all art. 3)

It is also made clear that “in the conduct of the full overview in the area of education, the Association/Community shall fully abide by the Constitution and legal system of the Republic of Kosovo”. Similar articles exist for health care, and other areas.

The bodies of the association would be an assembly, a president and vice-president, an (advisory) council, whose 30 members should reflect the ethnic composition of the member municipalities, a board with 7 members, reflecting the ethnic composition of the member municipalities, and an appeals and complaints office. Nothing of this contradicts Kosovo’s constitution or applicable law.

The association will have its own budget. Its “expenditures shall be subject to audits by the competent authorities, including thy the Auditor General of Kosovo.” Funds can include “contributions, grants, donations, as well as financial support from other associations and organizations, domestic and international, including the Republic of Serbia.”

Central government institutions will have a control function: “The Government and Auditor General of Kosovo shall receive each annual integrated budget of the Association/Community prior to its approval. The Government and the Auditor General will conduct a review of the draft budget for compliance with the Association/Community’s objectives and functioning of its bodies as defined by this Statute.” Within one year of the adoption of the Statute, a review of its implementation will be conducted by the Government. In case of disagreements between the government and the association, the government will submit the issue to the constitutional court.

The ASM statutes should be agreed on and adopted by a constituent assembly of the association/community in accordance with the Law on Ratification of the First Agreement and the Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo, then enacted by a legal act of the Government of Kosovo, receiving the power of a Government regulation under the Kosovo legal system upon review by the Constitutional Court.