Suspend Russia! The Council of Europe and the new cold war

- “Every right to retaliate”

- How the League of Nations died – 1936

- Russia and the Council of Europe

- When Blackmail worked

- Escalation – Memorial, Navalny and Russian elections

- Appeal: Vote now on Russian suspension

Dear friends,

On Monday, 21 February 2022, Russian president Vladimir Putin declared war on the principles enshrined in core treaties on which European stability is based: the Statute of the Council of Europe and the European Convention on Human Rights. Russia ratified these. If they are to remain credible then the member states of the Council of Europe must now react and suspend Russia for violating its most solemn commitments.

The Council of Europe was created in 1949 as a club of democracies. The idea behind it was to help democracies – young and old - remain democracies, through the Convention of Human Rights, the court, peer reviews and debates. One of the spiritual fathers of the Convention, Pierre-Henri Teitgen, a French resistance fighter and later minister of justice, explained:

“Democracies do not become Nazi countries in one day. Evil progresses cunningly, with a minority operating, as it were, to remove the levers of control. One by one, freedoms are suppressed, in one sphere after another. It is necessary to intervene before it is too late. A conscience must exist somewhere which will sound the alarm in the minds of a nation menaced by this progressive corruption, to warn them of the peril.”

For this to work each member state must collaborate sincerely and effectively. In the case of today’s Russia the opposite is true. The Council of Europe must therefore protect itself from its subversive influence and sound an alarm. It has the tools to do so. It now needs the will.

Eastern Ukraine – an eight-year long war

“Every right to retaliate”

The core of Putin’s 21 February message is a threat: Russia is forced to “retaliate” militarily against its many enemies, starting with those in Ukraine:

“Those who embarked on the path of violence, bloodshed, lawlessness did not recognize and do not recognize any other solution to the Donbass issue, except for the military one.”

This crisis, Putin makes clear in his speech, is not only about the Donbass region in Eastern Ukraine. Ukrainian identity is itself a fraud, the result of communist scheming: “Modern Ukraine was entirely created by Russia, more precisely, Bolshevik, communist Russia.” Putin warns that this communist-created identity must not survive: “We are ready to show you what real decommunisation means for Ukraine.” Putin adds that there is no Ukrainian tradition of statehood, that its current leaders had “seized power” in Kyiv, that they were manipulated by the United States to threaten Russia. This was all part of an existential struggle forced upon Russia by a wide alliance of enemies:

“There is only one goal – to restrain the development of Russia. And they will do it, as they did before. Even without any formal pretext at all. Just because we exist.”

In response to this, Russia has “every right to take retaliatory measures to ensure its own security. That is exactly what we will do.” Further bloodshed is thus inevitable: “All responsibility for the possible continuation of the bloodshed will be entirely on the conscience of the regime ruling on the territory of Ukraine.”

This is a turning point in 21st century European history: the supreme leader of a major nuclear power declares openly that his country is surrounded by enemies and that deploying Russia’s military to destroy artificial states and false national identities is inevitable retaliation. What writer Ed Lucas described in a book in 2008 as “The new cold war” is turning into a hot war against one of Europe’s most populous democracies.

Ed Lucas in 2008

At the same time, Putin made clear that this is also a struggle over values. His reasoning is familiar: historic grievances justify military aggression. Might makes right and powerful countries have the right to occupy those who are weaker.

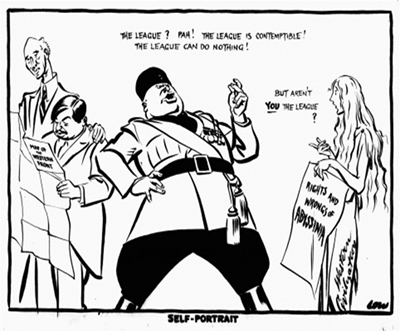

How the League of Nations died – 1936

In October 1935 Benito Mussolini told his compatriots that Italy had the right to invade and occupy one of the last African states that had not yet been colonised by European powers: Ethiopia (then known as Abyssinia).

It was a matter of justice. Italy, the Duce explained, had been promised a “place in the sun” for fighting along its allies during World War One. However, Italian sacrifice was followed by betrayal:

“…how many promises were heard? But after the common victory … when peace was being discussed around the table only the crumbs of a rich colonial booty were left for us to pick up.”

The time had come to give a military answer to those “who wish to suffocate us.” Mussolini dismissed the idea that his illegal invasion might lead to sanctions:

“I refuse to believe that the authentic people of France will join in supporting sanctions against Italy … I refuse to believe that the authentic people of Britain will want to spill blood and send Europe into a catastrophe for the sake of a barbarian country, unworthy of ranking among civilized nations … To economic sanctions, we shall answer with our discipline, our spirit of sacrifice, our obedience. To military sanctions, we shall answer with military measures. To acts of war, we shall answer with acts of war.”

In October 1935 the Italian army invaded Abyssinia. In the same month the Abyssinians appealed to the League of Nations for help.

The League condemned the attack. All League members were ordered to impose economic sanctions on Mussolini’s Italy. Then all resolve faltered. Sanctions were half-hearted. They did not include vital materials such as oil. Britain kept open the Suez Canal, crucial for the supply of Italy’s armed forces. In December 1935 the British Foreign Secretary and the French Prime Minister met and presented a plan that gave large areas of Abyssinia to Italy. Mussolini accepted the plan.

The capital, Addis Ababa, fell in May 1936 and Haile Selassie was replaced by the king of Italy. Somaliland, Eritrea and Abyssinia became Italian East Africa. International involvement was a failure. Autocracies everywhere were encouraged. The League of Nations was a corpse even before it perished, its legitimacy and credibility destroyed.

Russia and the Council of Europe

Will the widening of the war against Ukraine be for the Council of Europe what the Abyssinian crisis of 1936 was for the League of Nations? When Russia joined the Council of Europe in 1996, more than a quarter century ago, it committed itself to the values enshrined in its Statute and in the European Convention on Human Rights.

The Statute of the organisation is clear:

“The aim of the Council of Europe is to achieve a greater unity between its members for the purpose of safeguarding and realising the ideals and principles which are their common heritage and facilitating their economic and social progress.”

These ideals and principles are:

“the pursuit of peace based upon justice and international co-operation …;

the spiritual and moral values which are the common heritage of their peoples and the true source of individual freedom, political liberty and the rule of law, principles which form the basis of all genuine democracy.”

Membership was open to democracies committed to the pursuit of peace, to political liberty and to the rule of law. This excluded Spain and Portugal when they were autocracies. No communist people’s democracy was a member of the Council of Europe. This also led to the departure from the organisation of Greece after a miliary junta took power in 1967.

When Greece left the Council of Europe – junta in 1967

When the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) process was launched in the 1970s – which led to the OSCE after the end of the Cold War – it was to create a platform for dialogue between democracies and autocracies … although there was a non-binding commitment to values in the Helsinki Final Act, renewed in the 1990 Charter of Paris.

OSCE vs the Council of Europe: forum for dialogue vs. club of democracies

The Council of Europe, however, was never meant to be a mere forum for dialogue. It was to be a beacon for human dignity uniting democracies that had learned lessons from the tragic 20th century: each freely joining member holding the others to account for the respect for human rights and democratic norms.

After Russia joined the Council of Europe, it was given the benefit of the doubt for a quarter of a century. This was based on the hope that, over time, it would embrace the values of the institution.

However, instead of the Council of Europe changing Russia, this biggest member state changed the Council of Europe. It subverted the very idea that member states submit themselves to a European Court on Human Rights. It threatened other members and used blackmail against the institution itself. And like Mussolini in the League of Nations, Putin’s Russia got its way until now.

When Blackmail worked

In February 2014, the Ukrainian government led by Viktor Yanukovich was ousted after months of peaceful protest culminated in snipers killing demonstrators in the centre of the Ukrainian capital. Within weeks Russia annexed Crimea and precipitated a conflict in the Eastern Ukrainian region of Donbass that has already claimed some 15,000 dead.

In April 2014, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) suspended the right to vote of members of the Russian parliamentary delegation for a limited period. It was a very mild response in the face of so brazen a violation of another member state’s territorial integrity. PACE might have gone further and revoked the Russian delegation’s credentials, effectively expelling it from the Assembly altogether. But PACE chose not to do so.

Then an international investigation accused Russia of responsibility for the downing of a Malaysian passenger plane that left from Amsterdam, killing more than 200 (mostly Dutch) passengers; a chemical-weapons attack, which killed a British citizen in Salisbury; and repeated cyber-attacks on other Council of Europe member states.

In the Council of Europe, however, Russia played hard-ball, assuming that the organisation’s main players – key member states like Germany and France, represented in the Committee of Ministers, a majority of members of PACE and the Secretary General – were more interested in Russia’s continued membership (and funding) than it was itself.

Whose Council? Leonid Slutsky

Russia refrained from presenting the credentials of its delegation after 2015, excluding itself from PACE, and then posed conditions for its return. In October 2016, Leonid Slutsky, Chairman of the International Affairs Committee of the Russian Duma, formulated Russian demands, insisting: “Russia will return [to PACE] only if certain decisions are changed.”

In summer 2017, Russia resorted to financial blackmail, refusing to pay its financial contribution to the organisation “until full and unconditional (!) restoration of the credentials of the delegation of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation in PACE.”

Ilves and Kubilius: “Do not give in to blackmail”

Concerned Europeans, including Toomas Hendrik Ilves, former president of Estonia, and Andrius Kubilius, twice prime minister of Lithuania, sent a letter to the Council of Europe. They warned against PACE making a terrible mistake:

“We call upon the ruling elites of all CoE Member States not to allow the demise of the organization. History will judge harshly those who give in to blackmail from undemocratic societies where the rule of force is above the rule of law.”

ESI warned against giving in to Russian blackmail to change rules under pressure in many newsletters and presentations.

October 2018 – ESI paper: “Negotiating with a pointed gun”

ESI’s John Dalhuisen wrote in June 2019:

“A curious and undignified drama played out at the Council of Europe in Strasbourg this week, as parliamentarians from across the continent agreed to change the organisation’s rules in order to end a four year stand-off with Russia and pre-empt its threatened departure.

The story is so peculiar that it is best described by analogy. Imagine a schoolboy football match in which a notorious bully, and serial fouler, storms off after being whistled once too often. The bully, the largest and dirtiest player on the pitch, then stands on the side-lines insisting he will only come back and play if the rules are changed to get rid of penalties. Most of the other players agree. Some of the smaller, most kicked about players complain about this. But they are ignored. They are told the changes are good for the game of football and assured that the player will be less inclined to foul if he cannot be punished for doing so. The player returns and the game resumes.”

Alexey Navalny, the most prominent member of the Russian opposition in the last decade, saw an attempt on his life in August 2020 with Novichok, a chemical agent developed by the Soviet military. In December 2020 Navalny posted a video of a phone call he had made, tricking one of the agents involved in the operation to kill him into admitting to this on tape. The agent explained on the phone that Navalny had only survived due to the unplanned interruption of his flight and quick treatment.

Today Navalny is a political prisoner. Another former opposition leader, the former chess-master Garry Kasparov, is in exile in New York City, from where he published a grim warning about Putin's Russia in his book Winter is Coming. Former deputy-prime minister Boris Nemtsov was assassinated near the Kremlin in 2015.

April 2021 Interview Die Welt – “Russia wants to show that everything can be bought”

Escalation – Memorial, Navalny and Russian elections

The Russian state has occupied part of the territory of one fellow member of the Council of Europe (Georgia) and annexed part of another (Ukraine). It tolerates neither protest, nor political opposition. It locks up its critics. It kills perceived enemies, both at home and abroad.

The Council of Europe has bent over backwards to accommodate Russia in recent years, arguing that its membership gives Russian citizens access to the European Court of Human Rights. In fact, the European Convention of Human Rights obliges member states of the Council of Europe “to abide by the final judgment of the Court in any case to which they are parties.” Russia’s track record here is appalling, the second-worst among all member states, after Azerbaijan: it has fully implemented only a quarter of the most important cases it has lost, none of which concern the rights to freedom of expression, the right to protest, political arrests or killings, which is why the same violations keep on happening.

Access to the European Court on Human Rights is of little value if all its most important rulings are systematically ignored. In 2021 we pointed out that in its treatment of Navalny “Russia has shown contempt for the court. When the court ordered Navalny’s immediate release as an interim measure on 16 February 2021, one year ago, the Russian justice minister responded that this request would not be met because it was ‘baseless and unlawful’”.

And things kept getting worse, even before the recent escalation over Ukraine. Developments in the past year include:

- legal attacks against the human rights organisation Memorial to close it down,

- openly fraudulent parliamentary elections in 2021,

- another political trial against the imprisoned opposition politician Alexey Navalny,

- ever increasing repression of the few remaining independent media,

- repeated cyberattacks against Council of Europe members, and

- findings by a German court that the Russian state was responsible for another contract killing in Berlin.

In January 2021 German Social Democrat and a prominent member of PACE, Frank Schwabe, warned:

"the litmus test is whether the Russian Federation will allow the European Convention on Human Rights to protect its citizens accordingly … this is our red line … And if, at the end of the day, you are of the opinion that Russia is not cooperating there, then there can only be the possibility of saying: all in or all out. Then it cannot be the case that Russia stays on the Committee of Ministers and does not cooperate here."

As Russia is clearly not cooperating, the Committee of Ministers must act.

They must decide – member-states in the Committee of Ministers

Appeal: Vote now on Russian suspension

The Council of Europe is a vital institution. It must not meet the fate of the League of Nations. It is time that the Committee of Ministers draws a red line.

Article 3 of the Statute of the Council of Europe commits all members to “accept the principles of the rule of law and of the enjoyment by all persons within its jurisdiction of human rights and fundamental freedoms, and collaborate sincerely and effectively in the realisation of the aim of the Council…”

Article 8 stipulates that “any member of the Council of Europe which has seriously violated Article 3 may be suspended from its rights of representation and requested by the Committee of Ministers to withdraw.…”

The Committee of Ministers should give Russia a simple choice: withdraw Russian troops from Ukraine and other member states, where they are based without these countries’ agreement and implement judgements by the European Court of Human rights, including the judgements on Navalny … or face suspension. A decision on suspension would require a two-third majority. This should be put to the vote now.

Putin’s declaration of war this week is not just a military one. Putin does not believe in an international order based on the cooperation of sovereign, rights respecting democracies. But these are the very values of the Council of Europe. He is prepared to use force to win a bigger ideological battle.

This is a moment of reckoning. The member-states of the Council of Europe have three options:

- No strong response. This is what Russian politicians demand and expect. This is what happened so far.

- A slow response that takes years, by using a new mechanism agreed to in February 2020 for dealing with "the most serious violations of fundamental principles." (more on this here).

- A strong and immediate response by the Committee of Ministers, based on the Statute of the Council of Europe, leading to Russia’s suspension in case of continued non-compliance.

Economic sanctions are not enough – a battle of ideas and values must also be won. The Committee of Ministers should make clear: what is at stake here is a vision of how democracies in Europe operate, within and beyond their borders. It is a vision linked to legally binding obligations. Violating solemn commitments must have consequences.

Best regards,

Gerald Knaus

The European Stability Initiative is being supported by Stiftung Mercator

ESI proposal: The Council of Europe and Russia – Countries blatantly violating its rules should be suspended

ESI proposal: Caviar Diplomacy – Why every European should care