Macron, Italy and the mirage of mass return

- Paris and Berlin – what everyone agrees on

- Elephant in the room – impossible large-scale returns

- The human costs of deportation

- Italy – a deadly magnet

- What is needed: learn from the Dutch

- Moral realism and Italian policy

- Time to act – in Paris, Berlin and Rome

Dear friends,

In 2017 four countries – Germany, Italy, France and Greece – received 509,000 asylum applications, 72 percent of the total in the European Union. These four countries have the strongest interest in a functioning European asylum policy. But can Berlin, Rome, Paris and Athens agree on what such a policy should aim to do? What values it should be based on? And what instruments are needed to implement whatever is decided?

The current policy debate on migration and asylum in the key European capitals remains deeply confused over both values and instruments. Without clarity of thought no effective and humane policy will ever emerge.

Three new publications:

The Italian Magnet – Deaths, arrivals and returns in the Central Mediterranean (13 March)

How Italy can combine migration control with human rights (13 March)

"Amsterdam in the Mediterranean" – How a Dutch-style asylum system can help resolve the Mediterranean refugee crisis (26 January)

Paris and Berlin – what everyone agrees on

Emmanuel Macron, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (CDU) and Manuela Schwesig (SPD)

In September 2017 French president Emmanuel Macron made a passionate plea for a "Europe that protects" at Sorbonne University. There he argued that the EU needed to be able to "protect borders effectively", "take in those eligible for asylum" and "quickly return those not eligible."

In March 2018, immediately after forming a new coalition government, German Christian Democrats and Social Democrats agreed on the same principles: that "the intake of refugees is a humanitarian obligation, but those who do not receive permission to stay have to be returned" (Manuela Schwesig, deputy leader of the SPD); that "asylum law is a coin with two sides" and that some will have to leave the country, if necessary with force (Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, secretary general of the CDU). Germany's new interior minister Horst Seehofer promised to present "a master plan for faster asylum procedures and consistent returns".

This is today the common sense on asylum, shared in Berlin and Paris: offer asylum to those who need it, return those who do not need it, discourage irregular arrivals by boat. However, this common sense does not answer two basic questions essential for implementation:

How will those who do not need asylum be returned (if for many years already all EU states have failed to return most of those who arrive)?

How would those who need asylum reach the EU (if irregular arrivals by boat are successfully discouraged)?

There are two fundamental problems raised by the 509,000 asylum applications in Germany, Italy, France and Greece. First, perhaps 200,000, perhaps more, of these are likely not to receive international protection; but of those, few will ever be returned, and then most only after a long time. Second, among those who will get refugee status a significant group will have had to risk their lives crossing into the EU with smugglers. This policy comes at an enormous human cost: more than 3,000 drowned in 2017 in the Mediterranean trying to get to Europe.

Current EU debates start from the polarising question of distribution (relocation) of asylum seekers once they are already in the EU. This is a mistake. Instead governments need to work on credible policy answers on the basic issues of return and regular access. Legal access and strategic fast returns need to be linked creatively for Macron's vision to be realised.

Elephant in the room – impossible large-scale returns

The elephant in the room when discussing migration is the inability of EU states to return those who have no right to stay. This includes, importantly, almost everyone who arrived in Europe irregularly by boat in recent years.

This is not new. On the contrary, every time an EU member state has tried to return many, against their will, to countries with no interest in their return, the result has been failure. It is true for citizens of Senegal returned from Italy to their home country (readmission), for Afghans returned from Germany to Italy (Dublin returns) or for any asylum seekers transferred from Italy to other EU countries (relocation). It has always been hard to move people inside the EU; it is even harder to move people outside the EU.

Take the EU Dublin system. This never really worked as foreseen, but in recent years it has broken down completely. Between 2014 and 2016 there were 110,000 requests for Dublin transfers from the rest of Europe to Italy. Actual transfers in these three years: 8,000. 102,000 people lost at least six months each, the equivalent of 51,000 years of life-time, waiting around for no reason.

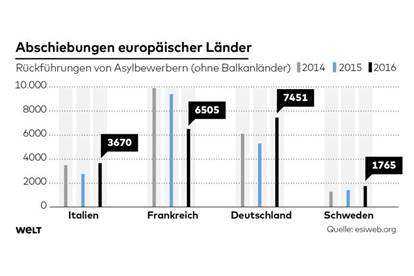

Take the recent German experience. Against the background of record arrivals of asylum seekers the German government announced, in late 2016, a "national effort" to return those with no right to stay, a national "Abschiebungsoffensive" (deportation offensive).

In summer 2017 we pointed out that in 2016 Germany managed to return very few people (7,451) to countries other than the Western Balkans, who have a strong interest to take back their citizens to preserve visa liberalisation. This is not a specific German failure; returns were similarly low from France, Italy or Sweden. We predicted that this was not likely to change. DIE WELT reported on ESI's analysis on its front page:

What has happened since? In 2017 Germany received 222,560 new asylum applications. In November that year the German Ministry of Interior provided a detailed breakdown of forced returns in the first nine months of that year:

The total of returns was 16,700. 8,624 were returned to the Balkans. 4,589 were transferred to other EU/Dublin partners; 1,609 went to Eastern Europe (mostly Moldova and Georgia, which – like the Balkans – enjoy visa free travel to the EU and thus cooperate); 1,014 went to three North African countries (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia).

864 were returned to the rest of the world. In these nine months Germany issued orders to leave to 7,325 Afghans, 4,955 Pakistanis and 4,126 Nigerians. Actual deportations during this period: 80 Afghans, 139 Pakistanis and 71 Nigerians.

The human costs of deportation

This raises a political and moral dilemma: what is the justification to return a select few unfortunates, when most people never leave? A few who, because of slow procedures, may have already spent years in the EU trying to build a new life? What is the point of deporting asylum seekers like Taibah Abbasi?

Taibah Abbasi is an 18-year old Afghan woman who grew up in Iran. In 2012 Abbasi's family received protection in Norway. Now, in March 2018, the family is about to be deported. Abbasi has attended school in Norway for six years. Norway had been generous to refugees, like her family, for many years. It has serious asylum authorities and independent courts. Returning her is legal; but does it make any sense?

Returning a few hundred people a year, who will often have spent years in Europe already, will not stop others from trying to come. Meanwhile, the human costs are high for some individuals. A few years ago Swedish doctors reported on hundreds of refugee children who fell unconscious after being informed that their families would be deported (Uppgivenhetssyndrom, or resignation syndrome). The threat of deportation, like the experience of long-term detention, can be deeply traumatizing.

The moral calculus changes when those to be deported have committed crimes or pose a threat. Current German policy – to return only those Afghans whose asylum claims are rejected and who committed crimes or pose a credible threat – addresses this. The moral calculus also changes when returns are few, quick, follow a fair procedure and by deterring others might save lives. But what purpose is served by returning Taibah Abbasi? In fact, many citizens in European democracies feel as uncomfortable with forced returns of individuals who pose no threat and who have become their neighbours as they might feel about open borders. This empathy is an asset, and a credible policy could build on it.

Today only far-right parties benefit from the repeated failure of promised mass deportation. Promises that cannot be kept make mainstream governments look weak. Returning far fewer people than arrive in the meantime across uncontrolled borders makes them look ineffective. Returning a few who pose no threat makes them appear unnecessarily cruel. And yet, governments do all this because they cannot think of a better plan that majorities will back.

Return realists recognise that forced returns are costly: to those who are moved, to the countries carrying them out and to the countries receiving those to be returned. For this reason realists focus return efforts on:

- those who pose a threat

- those whose return has the biggest impact on discouraging future irregular arrivals of people not in need of protection.

The latter requires returns to take place after a short, quick asylum procedure, within weeks of arrival. It requires concrete incentives for countries of origin to cooperate fully on these returns. The shared goal of both sending and receiving countries should be to reach their objectives with the least necessary number of returns, precisely because returns are costly and painful.

A realistic approach acknowledges that some quick returns can reduce irregular arrivals. To achieve this without sacrificing the quality of asylum determination procedures requires a genuine European effort. A slow asylum system – as in France, Germany, Italy or Greece – will not achieve this deterrent effect.

To realise president Macron's vision the key lies not in France or Germany, but in European cooperation of a new kind in the Mediterranean – with Italy and with Greece.

Italy – a deadly magnet

Majorities in all European democracies want to see irregular arrivals – especially the arrivals of boat people with the help of smugglers – dramatically reduced. This includes most Italians.

In recent years Italy has faced an unprecedented number of arrivals from Africa. There were 130,180 asylum applications in 2017. Fewer than 13,000 people received international protection that year in Italy. 46,992 asylum claims were rejected at first instance level (58 percent). And yet, in 2017 there were only 5,700 returns (both by force and voluntarily).

In Italy today getting a final rejection can take years. In 2016 an official study found that it took 403 days to receive a first instance decision and up to 1,813 days, or almost 5 years, to receive a final decision. And the longer the process takes, the stronger the case to offer some form of legal stay – in Italy's case mostly humanitarian protection.

The result is that many people stay in legal limbo for a long time; and that almost everyone who reaches Italy by boat will stay in the EU for years, independently of any initial protection need. This reality draws people into crossing the Sahara, into the murderous cauldron of Libya and onto dinghies. It contributed to 13,500 deaths by drowning in the past four years alone, and to rapes, murders and abuse along the path to Europe.

More Details: The Italian Magnet – Deaths, arrivals and returns in the Central Mediterranean (13 March 2018)

What is needed: learn from the Dutch

In the past year ESI analysts studied the Dutch asylum system, which combines quality, free legal support and speed at both the first instance and the appeals stages. The problem is that the Dutch system is far away from the EU's external border where it would be needed most. After a quick decision the Dutch struggle – like all others – with returning those who are rejected.

If Berlin and Paris want to bring about a sharp reduction of irregular arrivals to the Schengen area from Africa they need to sit down with the next government in Rome and develop a European pilot project that brings the Dutch system to the Mediterranean.

Italy should be able to invite other EU partners to help with carrying out quality asylum decisions within days, and with returning those who are found not to need protection in the EU as part of a collective European effort within weeks. Italy would need to ensure enough front-loaded judicial capacity – with special sections in courts or judicial appeals panels – that decide on appeals within a few weeks, as quickly as courts in the Netherlands.

Fast procedures alone are not enough. Paris, Berlin and Rome should also appoint a senior political figure as special envoy to negotiate return arrangements with African countries of origin. These countries need concrete incentives to want to help identify and take back their citizens not in need of protection, and who arrived after an agreed date. If this is done, it will not actually require many people to be taken back because the announcement of this policy and the first returns will deter others.

More details: "Amsterdam in the Mediterranean" – How a Dutch-style asylum system can help resolve the Mediterranean refugee crisis (26 January 2018)

Moral realism and Italian policy

ESI Senior Fellow John Dalhuisen – ESI Study visit to Ter Apel asylum center (Netherlands)

In recent decades, every time the number of arrivals by boat has increased, Italian public opinion has shifted to demand measures to reduce them: in the 1990s, in 2002, 2008, 2011 and again in the last few years. Responding to this pressure, the Democratic Party government concluded a Memorandum of Understanding on migration with the UN-backed interim government in Tripoli in February 2017. Italian interior minister Marco Minniti personally met with Libyan tribal leaders and mayors to enlist their support to stop people setting out across the Mediterranean.

This policy has reduced the number of lives lost at sea. However, the Libyan coast guard brings those it intercepts to detention centres where conditions are inhumane. Abuse is common. The rest of the EU has backed Italy's Libya policy. NGOs and UN agencies have criticised it sharply. And yet, as Italians headed to national elections earlier this month no major political party was opposing Minniti's policy.

In an article following the recent Italian elections we suggested that the next Italian government should propose to its European partners a realistic plan with four elements:

- A common effort to ensure sufficient search-and-rescue capacity beyond Libya's territorial waters.

- Any Western support to the Libyan coast guard and the Libyan authorities must be linked to a clear condition: that anybody intercepted by its boats and taken back to Libya should be offered immediate evacuation to Niger by the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The numbers involved make this possible: In 2017, the Libyan coast guard intercepted fewer than 1,500 people a month on average. In Niger, those who choose not to apply for asylum should be offered assisted return to their countries of origin via the IOM. Those who do apply for asylum should be resettled to a safe country if found to be in need of protection.

- Securing agreements with key African countries of origin for failed asylum seekers arriving after an agreed date. These countries should be offered an annual contingent of regular visas, not just by Italy, for work or study.

- A quick and fair asylum process that should seek to award a protection status or move to deport those found to have no claim within two to three months at most.

All this would certainly require the financial and administrative support of other EU countries, which should relocate recognized asylum seekers. It would not be cheap to run, or easy to set up, but as a joint European effort, it is doable.

Such a system would benefit Italy, France, Germany and the whole of the EU. It would sharply reduce new arrivals, without calling for impossible large-scale deportations. It would achieve control, save lives and reduce human suffering.

More details: How Italy Can Combine Migration Control With Human Rights

John Dalhuisen and Gerald Knaus (13 March 2018)

Time to act – in Paris, Berlin and Rome

In his Sorbonne speech in September 2017 French president Emanuel Macron stressed that France would not "leave some of our partners submerged under massive arrivals, without helping them manage their borders."

"Europe is not an island. We are here, and our destiny is bound to that of the Middle East and of Africa. Faced with this challenge, it is once again at European level that we need to act. Only with Europe can we effectively protect our borders, take in those eligible for asylum decently, truly integrate them, and at the same time quickly return those not eligible for such protection."

In his New Year's address in December he called it a "moral duty" for France to give asylum to those in need, but added: "We cannot welcome everyone, and we cannot act without rules … I will work for our country to defend humanity and efficiency." On 14 March, Macron told the German daily FAZ: "I will fight for asylum applications to be processed faster, but also for those who are not entitled to asylum to leave our country faster."

What emerges from Macron's speeches are clear objectives: to combine control with empathy, asylum with return, French initiatives with European solidarity. These are the right promises, but risky ones if they are not followed up on. Electorates across Europe have shown diminishing patience for governments that fail to deliver on promises, particularly when it comes to controlling migration. Conversely, the rewards for those who can implement a policy that combines control and empathy and dare to deliver on it, are likely huge.

What is still missing in Macron's proposals is a description of concrete instruments that take into account the experiences of recent years on returns. What is needed urgently is an informed debate in key capitals on these issues, followed by a joint effort, strongly backed by France and Germany, in Italy and Greece. With a new government in Berlin and following the recent Italian elections, the time is ripe.

Best regards,

Gerald Knaus

ESI's policy work and research on European asylum reform

is supported by Stiftung Mercator

On Taibah Abbasi: Norwegian teen fighting deportation

On Balkan asylum seekers: how European countries with faster asylum procedures reduced asylum applications from the Western Balkans: Saving visa-free travel – Visa, Asylum and the EU roadmap policy (2013), chapter 3.

On lessons from a surge in Montenegrin asylum applications in Germany in 2015: Montenegro: Germany's Balkan stipends (19 January 2016).

German papers on the ESI Rome Plan for the Mediterranean migration crisis in 2017:

Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung on 4 July 2017, discussing the migration crisis off the coast of Africa, concluded that the Rome Plan would likely be controversial, but "that it could work".

An editorial in Süddeutsche Zeitung on 12 July noted that "in the long run, this could be the only solution that would leave something of a basic right of which Europeans are very proud: the right to asylum".

A front-page article in the weekly Die Zeit argued on the same day (12 July): "Better that acting in moral panic is coolly searching for a plan offering something of real interest to states like Nigeria and at the same time meeting Europe's interest in a reduction of refugee numbers, less deaths in the Mediterranean, and a decent asylum procedure. The think tank European Stability Initiative has put forward a proposal which is as clever as it is feasible: the 'Rome Plan'."

Italy: Sea arrivals, asylum applications, and first-instance decisions

|

Arrivals |

Applications |

Decisions |

|||

|

2010 |

4,406 |

12,121 |

14,042 |

||

|

2011 |

62,692 |

37,350 |

25,626 |

||

|

2012 |

13,267 |

17,352 |

29,969 |

||

|

2013 |

42,925 |

26,620 |

23,634 |

||

|

2014 |

170,100 |

63,456 |

36,270 |

||

|

2015 |

153,842 |

83,970 |

71,117 |

||

|

2016 |

181,436 |

123,600 |

91,102 |

||

|

2017 |

119,369 |

130,180 |

81,527 |

||

2017 EU asylum applications – top 10 countries

|

Country |

Applications |

|

Germany |

222,560 |

|

Italy |

128,850 |

|

France |

98,635 |

|

Greece |

58,705 |

|

United Kingdom |

33,780 |

|

Spain |

31,120 |

|

Sweden |

26,325 |

|

Austria |

24,275 |

|

Belgium |

18,340 |

|

Netherlands |

18,210 |

|

18 member states |

43,800 |

|

Total |

704,600 |

More core facts here: www.esiweb.org/corefactsitaly

More ESI reports here: www.esiweb.org/refugees