Croatia's European rebirth: a story of leadership

- Why did Croatia persist?

- Franjo Tudjman's vision

- Leadership

- A European Croatia

- Telling Croatia's story

Dear friends of ESI,

In the end it seemed almost inevitable.

This weekend two thirds of voters supported Croatia's accession to the European Union as its 28th member. The referendum came after national elections in December in which all main parties had backed joining the EU. It concluded a decade in which all Croatian governments had proceeded on the assumption that there was no alternative to meeting the conditions put forward by the EU to become a full member.

Croatia's negotiating framework, set in place after the rejection of the constitutional treaty in France and the Netherlands, was more demanding than for any previous applicant. The EU insisted on handing over generals responsible for Croatia's battlefield victories in the 1990s to the ICTY in The Hague. Croatia had to demonstrate that its judicial system could put on trial and convict highly placed officials. It also had to accept binding arbitration concerning its borders with neighbouring Slovenia in the face of what was widely viewed in Croatia as Slovenian blackmail.

Some noted that less than half of all eligible voters participated in the referendum; in fact, given problems with a large number of "dead souls" in the voting registry, and the fact that a large number of Croatian citizens living abroad also did not care to vote, the percentage of resident voters in Croatia who participated appears to have been above 61 percent and thus higher than in the referenda on EU accession in Hungary, Slovenia and Poland. Only 6,123 Bosnian Croats cast ballots - or 2.3 percent of all 413,000 Croatian voters supposedly resident there.

Why did Croatia persist?

Croatia submitted its application in early 2003 to the Greek EU presidency. Europe has since seen a rise in scepticism about enlargement, faced a deepening economic crisis and is even now struggling with an existential challenge in the Euro zone. The fate of Greece and the problems of other members also undermined the confidence that accession was a guarantee of future prosperity.

So why did Croatia's leaders persist? Why did a government led by the HDZ (Croatian Democratic Union) co-operate with an international criminal court (the ICTY in The Hague) which concluded that Croatia's founding president and first leader of the HDZ, Franjo Tudjman, had been at the helm of a "criminal enterprise" to ethnically cleanse his country of Serbs? Why did HDZ-led governments create conditions in which independent prosecutors indicted a former HDZ prime minister, HDZ deputy prime minister, HDZ minister of defence, HDZ party treasurer, and a large number of well-connected managers in public companies?

And how did the national consensus on the need to implement even painful and costly reforms survive periods of delay, EU hesitation, and the perception of European double-standards? This consensus was put to the test continuously in the powerful parliamentary Committee for Monitoring Accession Negotiations, chaired by an opposition MP (Vesna Pusic), including 15 Croatian parliamentarians, representing all parliamentary parties, with every one of them holding a veto over the negotiating positions for each chapter. Why did not even one try to bring the process to a halt?

To understand this robust national consensus, the HDZ's perseverance and the opposition parties' sustained support to this effort, one has to recall the alternative most Croatians remembered: the situation of the 1990s, before their country embarked on its EU accession process.

Croatia's leaders persisted, because, in the end, they rejected the vision and the policies of the 1990s.

|

|

|

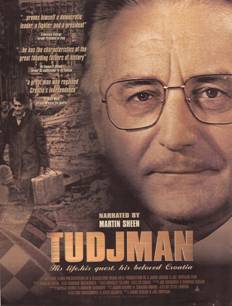

A film for the world, only once shown in Croatia - How Tudjman saw himself |

|

Franjo Tudjman's vision

In 1995, when the war in Bosnia ended, Croatia's president Franjo Tudjman looked like the biggest winner of the Yugoslav conflict. He had led newly independent Croatia through four years of war. By 1998 he had restored Croatian control over all of its territory. Croatia had a powerful army. It was seen as close to the United States. It also still had great influence in neighbouring Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Tudjman turned his attention to ensure that posterity would see him as he saw himself: a heroic father of the nation. He commissioned films and books on his life. He continued to record all of his conversations in the presidential palace. And yet, Tudjman's post-war vision of a bright future quickly came undone. After the Dayton Agreement had been signed he continued to undermine the statehood of neighbouring Bosnia, convinced that its borders were "historically absurd." He was surprised that his former allies expected him to stop funding Croatian extremists in Herzegovina. He had been an early supporter of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, convinced, as he told an associate, that "those who win wars are never tried." Then, in 1998, he realized that the ICTY was investigating atrocities committed by his forces, as well as his own role.

In 1997 the prime minister of Bulgaria, Ivan Kostov, told his parliament that Bulgaria would make every effort to join the European Union within a decade (and in 2007 Bulgaria did indeed join). Croatia did not follow. Tudjman chose isolation instead. In December 1998 he explained in a speech at the military academy that "even now The Hague (ICTY) prepares indictments against you, against us" and that in the face of this the country needed "a united military and people."

Tudjman died in 1999, just before he would have been indicted. No president except Turkey's attended his funeral. The tapes of his conversations in the presidential palace ended up not as proof of historic greatness but as evidence in The Hague.

Until today there is no monument in Zagreb of the man who saw himself as Croatia's George Washington. Soon after his death even his own party stopped evoking his name. And when it tried to draw on Tudjman's legacy in the most recent election campaign, it flopped.

|

|

|

|

Stipe Mesic – Ivica Racan – Ivo Sanader |

||

Leadership

Even after Tudjman's death, however, Croatia's EU accession was not inevitable. For this a succession of leaders had to make a strategic choice. They also had to take real risks.

The first to do so was Stipe Mesic, a two-time president and successor of Franjo Tudjman. Mesic outlined the vision of Croatia's EU accession in his inaugural speech. In September 2000, some of Croatia's most respected army generals signed an open letter warning that the prosecutions of wartime heroes for alleged war crimes should stop. Within hours Mesic stripped them of their positions. As he told ESI:

"It was not easy to send generals into retirement when everybody was afraid of a coup. But nothing happened. With the army, there is no negotiation."

This was a turning point for Tudjman's security apparatus and the investigation of war crimes.

Ivica Racan, Croatia's last communist leader who became prime minister after Tudjman's death, submitted Croatia's EU membership application in 2003. Racan also, crucially, ended Croatian support for hardliners in neighbouring Bosnia.

The most surprising role was played by Tudjman's successor at the head of the HDZ, however: the polyglot Ivo Sanader. Under his leadership the HDZ returned to power on a nationalist platform in late 2003. Once in charge, however, his government turned its back on Tudjman's legacy on all crucial issues that had kept Croatia isolated in the 1990s. Sanader intensified co-operation with the ICTY. He handed over all indictees still wanted by the tribunal, including senior generals. He included a Croatian Serb party in his coalition government. He continued to support Bosnia's territorial integrity. And he made EU integration the overriding priority for his government. In 2005 Croatia opened accession talks. In 2009 Croatia joined NATO.

Sanader's successor as prime minister, Jadranka Kosor (also HDZ), faced a different strategic choice. The EU insisted on serious reform of the judicial system. Kosor accepted its demands. Laws and rules were changed to empower prosecutors. A spectacular series of arrests and trials began. Investigators caught up with her predecessor, Ivo Sanader, who was arrested in 2010. They even caught up with her party. This was one reason HDZ lost control. It also was crucial to enable Kosor to sign the accession treaty in late 2011: these trials had convinced sceptics in the EU that change in the judiciary was real.

Today Ivo Sanader stands trial in Zagreb on charges of major corruption. Even his biggest political opponents note, however, that without his success in transforming the HDZ, turning its back to Tudjman's vision, Croatia would not have made the progress it did.

|

A European Croatia

Compared to where it stood in 1999, Croatia is undoubtedly a story of a successful transformation. It is also evidence that the strict EU negotiating framework, which will also be employed in for future accessions, can bring results.

A few weeks ago Vesna Pusic, for many years a crusader for EU integration in the Croatian parliament, today Croatia's new foreign minister, told ESI that

"If you look at Croatia the way it was ten, eleven years ago and the way it looks now, it is a different country in every aspect. I can say with absolute certainty that it is a different country because of the EU accession process."

Pusic also stressed:

"Our experience is that it is almost impossible for somebody to help you if you cannot help yourself first."

Croatia's is an experience that also other Balkan countries would do well to study.

(For a portrait of and interview with Vesna Pusic, including her take on Croatian lessons for other Balkan countries, go here. For an interview on the eve of the December 2011 elections with the incoming prime minister, Zoran Milanovic, go here.)

|

|

|

|

ESI analysts working on Croatia: Kristof Bender, Snjezana Vukic, Besa Shahini |

||

Telling Croatia's story

In coming weeks ESI will put a lot more on Croatia on our website. This is part of our Future of Enlargement Project run by ESI deputy chairman Kristof Bender and supported by ERSTE Foundation in Vienna.

We are preparing, led in Zagreb by ESI analyst Snjezana Vukic, a new documentary to be broadcast later this year within the award-winning Return to Europe series in co-operation with the Austrian Broadcasting Association ORF and Geyerhalter Productions.

Together with the Bosnian think tank Populari, ESI analysts, including senior analyst Besa Shahini, are analysing how the new negotiating framework for accession has worked to transform the Croatian administration in selected areas, with case studies of reforms in the vital environment and food safety sectors; exploring what it would take for other countries, including Bosnia, to follow suit (for more on this project go here).

There are many more lessons both the EU and the region can learn from Croatia's trajectory since 1999. The most important is reassuring in times like these: EU soft power and conditionality, linked to a credible accession process, remains a powerful motor of change even today.

Best regards,

Gerald Knaus

- ESI – Populari Project on lessons from Croatia's reforms for Bosnia

- Zoran Milanovic, Croatia's new Prime Minister (new ESI Interview)

- Vesna Pusic, Croatia's new Foreign Minister (new ESI portrait and interview)

- Stipe Mesic, former Croatian President (new ESI portrait)

- Ivica Racan, former Croatian Prime Minister (new ESI portrait)

- The Future of EU Enlargement webpage

- ERSTE Foundation