Albright on hope – Europe whole and free – An award – Our deal in the Aegean

- Fireworks in Central Europe

- Europe whole and free – also in the Balkans

- An award and an inspiration

- Our plan for the Aegean – 2016 lessons for 2022 borders

Dear friends of ESI,

In February 1949, Josef Korbel, a former ambassador of Czechoslovakia to the former Yugoslavia, who was then working as a diplomat at the United Nations in New York, wrote a letter to the U.S. ambassador to the UN.

Korbel explained that a coup, carried out by communists in Prague in early 1948, had made it impossible for him to continue to serve this regime. The letter concluded with a plea:

“I cannot, of course, return to the Communist Czechoslovakia as I would be arrested for my faithful adherence to the ideals of democracy. I would be most obliged to you if you could kindly convey to his Excellency the Secretary of State that I beg of him to be granted the right to stay in the United States, the same right to be given to my wife and three children.”

Four months later, Josef Korbel and his family were granted political asylum.

Fireworks in Central Europe

It was hard to imagine in that dark time, at the height of the cold war, that decades later Korbel’s daughter Madeleine would return to a Czechoslovakia where peaceful protesters had toppled the communist dictatorship established in 1948. Or that his daughter would welcome, in February 1990, the dissident, writer and political prisoner Vaclav Havel in the US as the new president of her former home country, urging his American hosts “to help the Soviet Union on its irreversible, but immensely complicated, road to democracy.”

Certainly, nobody would have predicted either that in 1992 Madeleine would herself become the US ambassador to the United Nations and then, in 1996, the first female US Secretary of State.

By the time Madeleine Albright moved into the State Department, Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union had dissolved peacefully, while Yugoslavia had broken apart in violence and war. Albright would now play a central role to bring about the Western integration of the new Central European democracies. In 1989, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland joined NATO as the first former communist members, with fireworks going off in Warsaw, Prague and Budapest.

Europe whole and free – also in the Balkans

This breakthrough opened new horizons for a new Europe, whole and free. As Albright wrote in her memoirs about that moment in history:

“Now, with the United States, NATO and Central Europe together as allies and friends, the boundaries of possibilities had been pushed back to a new and seemingly limitless horizon … the urgent question I faced was whether the Balkans could also be brought closer to the West. The answer, I was convinced, would depend on the success or failure of the Dayton Accords [in Bosnia and Herzegovina] … Dayton had affirmed the principle of a unified Bosnia, but it would take far more than a piece of paper to make that goal a reality.”

She feared at the time that too many European allies did not see the urgency of this:

“More and more pundits said the only realistic option was to partition Bosnia, with one segment joining Serbia, another Croatia, and the third becoming an international protectorate. Partition, as far as I could see, wouldn’t create stability, only a new fight over borders.”

A peaceful Europe, including a stable Balkans, had to be built on different foundations: “We had to insist that the new Europe be built on principles of democracy and respect for human rights, not ethnic cleansing and brute force.”

This required pressure, which Albright and the US administration were ready to apply, to help those refugees and displaced persons, who wanted to return to their former homes in Bosnia, to be able to do so. It required strong backing for the International Tribunal, including the support of NATO allies and soldiers, to bring indicated war criminals to trial. It required standing up to those, like Slobodan Milosevic, who were prepared to use brutal violence once again in 1998 and 1999 in Kosovo. It also required that citizens in the Balkans did not yield to the urge of revenge, as Albright explained to a crowd in Pristina following the end of the 1999 war:

“Democracy cannot be built on revenge … It must be a victory of those who believe in the rights of the individual over those who do not. Otherwise, it is not victory. It is merely exchanging one kind of repression for another.”

In summer 1999, Albright joined global leaders in the sport stadium in Sarajevo, which had been used for figure skating in the 1984 Olympics, to launch a Stability Pact for the Balkans. There was, she felt, a real opportunity to “close the door on the past and embrace a democratic future. We had, I thought, a real chance to transform the patterns of history and replace the whirlpool of violence with a steady forward current.”

I remember this moment well. By accident, I was also attending this summit, obtaining a pass to join the attendants on the floor of that big hall, where ice skaters used to move, while a friend was hectically drafting the concluding speech for the Finnish president. At that very moment, in that very city, we, a group of friends working for international organisations, had decided to create an NGO, the European Stability Initiative (ESI), over drinks in the garden of a Sarajevo restaurant. We had a big, quixotic ambition: to help, through analysis and reports and advocacy, realise the vision of a new Europe whole and free. A Europe, based on human rights and democracy. A continent, in which future war in South-East Europe becomes as unthinkable as it had become in Western and Central Europe.

After a tumultuous and troubling 2021, with instability and fear returning to the Balkans, with a European Union seemingly lost and bereft of ideas for its neighbours, and with the very real threat of a Russian aggression looming over Ukraine, that vision, expressed since 1990 by Havel and Albright, remains as urgent and relevant as ever.

An award and an inspiration

Madeleine Albright’s presentation on hope and persistence

In October 2021, the German Bundesakademie für Sicherheitspolitik - Federal Academy for Security Policy - kindly awarded me their Karl-Carstens Award 2021. This award is given every two years, so the Academy, for having “rendered outstanding services to communicate security policy issues and the idea of comprehensive security to the broader public.” There was a ceremony with music - Louis Armstrong and Coldplay – and a few speeches before (given the pandemic) a few guests in the historic seat of the Academy in Pankow in the former East Berlin. It took place in a hall that had hosted the round table leading to the negotiated end of autocracy in the GDR.

Karl-Carstens Award Ceremony 2021

In recent years the laudatory speakers at this event had been Ursula von der Leyen and Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer. This year’s laudatory speaker was Madeleine Albright, with a message about the West, the future of democracy and reasons for hope that reflected her life’s experience.

“Demagogues try to convince people to give up hope. We must not give up,” she insisted. The pendulum may swing between freedom and autocracy, but autocrats always face challenges to maintain their popularity. There are therefore good reasons to expect positive changes in the months and years to come:

“Despite the battering that democracy has endured, most people want to strengthen, not discard democracy.”

Albright noted that recently a misplaced sense of complacency about democratic stability has disappeared, and with it, unrealistic euphoria about democracy. But this must not lead to defeatism, cynicism or despair:

“We will not allow the peddlers of hate to shape our future. We will not allow them to hijack our institutions We will not abandon all what we have gained through decades of shared sacrifice. We will not remain silent, as demagogues strive to drain the meaning from words, and try to convince us that up is down, wrong is right and truth is whatever they want it to be.”

Albright said very kind words about ESI and our work since 1999. But her most important message was to all believers in democracy and human rights, in Europe and in the US:

“We must insist on the integrity, the importance of democratic values, the rights of majorities and minorities and the dignity of every human being. With these beliefs, there is no threat before us against which we will not prevail.”

Politics is hard, ideas and ideals always under pressure. Democracy invites setbacks. And yet, the experiences of Central Europe in recent decades – of Prague and Berlin, Warsaw and, indeed, the Western Balkans – have shown that the vision of democratic peace is no pipedream.

We want to thank Madeleine Albright for inspiring us to keep working on “one Europe, whole and free.” To quote a friend of hers, and our inspiration, Vaclav Havel, from February 1990: the improbable is possible, and sometimes it is for the (much) better.

“We are living in very extraordinary times. The human face of the world is changing so rapidly that none of the familiar political speedometers are adequate.

We playwrights, who have to cram a whole human life or an entire historical era in a two-hour play, can scarcely understand this rapidity ourselves. And if it gives us trouble, think of the trouble it must give to political scientists who spend their whole life studying the realm of the probable and have less experience with the realm of the improbable than us, the playwrights.”

My presentation on Berlin as a symbol of hope

Our plan for the Aegean – 2016 lessons for 2022 borders

“Warnings do not make our world better, actionable suggestions on how to improve it and how to prevent and avoid crises do.”Thomas de Maizière, former German Federal Minister of the Interior

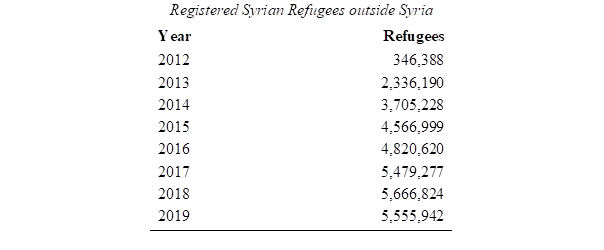

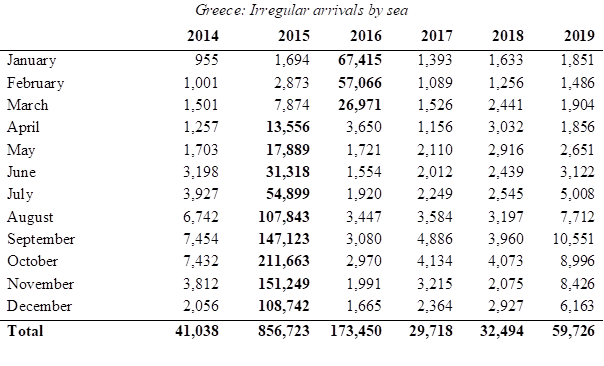

In autumn 2015, something extraordinary happened. Never before had so many people arrived irregularly in small boats to the European Union. The background was the biggest refugee crisis in the world since the 1970s, caused by the war that broke out in Syria in 2011. Initially, Syrians fled to neighbouring countries. Turkey thus became the country with the most refugees in the world.

On September 29, 2015, the Bavarian government noted that 169,400 refugees had arrived in one month. At this rate, 1.8 million would reach Germany in a year. A UNHCR Regional Coordinator stated in September, "I don’t see it stopping … maybe this is the tip of the iceberg." More people arrived irregularly in Greece in 2015 than had entered Europe irregularly from Africa altogether since World War II. The only comparable exodus across the Mediterranean since World War II was the flight of the French Pieds-noirs from Algeria at the end of the Algerian war of independence.

And then, it was suddenly over. On a Sunday evening, 6 March 2016, Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu made a proposal for cooperation to the Dutch Prime Minister and the German Chancellor at the Turkish Embassy in Brussels. This led to a joint declaration on 18 March. Legally, this EU-Turkey Statement was no more than a press release, but its impact was enormous.

In Brussels, 6 March 2016

In the twelve months before, one million people had reached the Greek islands. In the twelve months after, 26,000 did.

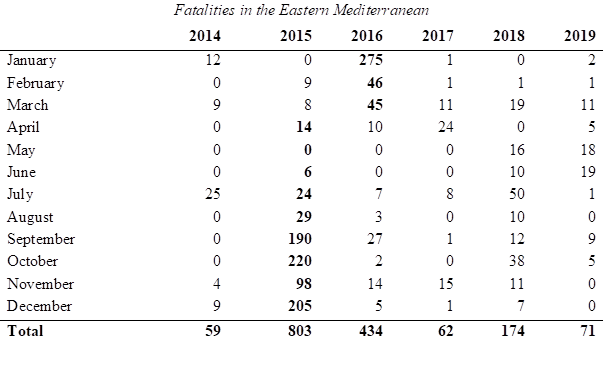

The number of people who drowned in the Aegean Sea also fell immediately, from 1,152 in the year before the declaration to 81 in the year after.

How had this declaration come about? What happened in Greece and Turkey in the years that followed? Why did the agreement fail at the end of February 2020? What can one learn from the sharp reduction in the number of deaths at sea? And importantly: What does this experience mean for the future of Europe’s borders, in particular for the ambitions expressed by the new German coalition government, in its coalition treaty reached a few weeks ago, to strike new agreements with partners in the future that can help to reduce irregular migration without illegal pushbacks and without violations of the right to asylum.

I wrote a chapter to answer these questions in the 2020 book “Which borders do we need? Between empathy and fear – Flight, Migration and the future of asylum.”

For those who do not read German, please find this chapter attached in English, for the first time:

Much about the March 2016 declaration was unprecedented. The EU mobilised the largest humanitarian aid in its history for refugees in a third country, six billion euros for Syrian refugees in Turkey. The Turkish Prime Minister, Ahmet Davutoğlu, expected to resettle hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees from Turkey. After many decades, Turkish citizens would be allowed to travel to the EU without a visa for the first time since the military coup in 1980, should Turkey fulfil further conditions:

“Once irregular crossings between Turkey and the EU are ending or at least have been substantially and sustainably reduced, a Voluntary Humanitarian Admission Scheme [for Syrian refugees] will be activated. EU Member States will contribute on a voluntary basis to this scheme.

The EU … will further speed up the disbursement of the initially allocated 3 billion euros under the Facility for Refugees in Turkey … Once these resources are about to be used to the full, and provided the above commitments are met, the EU will mobilise additional funding for the Facility of an additional 3 billion euro up to the end of 2018.

The fulfilment of the visa liberalisation roadmap will be accelerated vis-à-vis all participating Member States with a view to lifting the visa requirements for Turkish citizens at the latest by the end of June 2016, provided that all benchmarks have been met.“

In return, Turkey promised to take measures "to prevent new sea or land routes for illegal migration opening from Turkey to the EU". Most importantly, the Turks promised to take back anyone who reached the Greek islands from 20 March 2016. Greek authorities, in line with existing EU asylum law, would decide who could be sent back. The statement reaffirmed existing European law:

“All new irregular migrants crossing from Turkey into Greek islands as from 20 March 2016 will be returned to Turkey. This will take place in full accordance with EU and international law, thus excluding any kind of collective expulsion. All migrants will be protected in accordance with the relevant international standards and in respect of the principle of non-refoulement … Migrants arriving in the Greek islands will be duly registered and any application for asylum will be processed individually by the Greek authorities in accordance with the Asylum Procedures Directive, in cooperation with UNHCR. “

On 18 March, Angela Merkel declared in Brussels that the agreement would help "above all the people concerned, the refugees". The aid in Turkey would "combat the causes of flight". Merkel reiterated that she expected setbacks because "there are major logistical challenges … we have made a step forward, a very important step on the way to finding a sustainable solution to the issue, and not just a sham…"

As European borders have become ever more lawless in recent years, as pushbacks are becoming ever more systematic and open in 2021, and as the number of people drowning in the Mediterranean reached more than 1,800 in 2021, making this once again the deadliest border in the world, European policy makers and activists, who look for a way to combine control of irregular migration (which the new German government vows to reduce) with respect for human rights and the right to asylum (which this German government promises to defend) and with saving lives, might find revisiting this experience useful.

Of course, this is one (our) side of the story, and we look forward to more serious debate. In early 2022, we will also continue our series of essays on the future of the global refugee system launched in 2021:

Essay 1 - The promise and the agony – saving the refugee convention

26 May 2021

Adherence to the global refugee protection system has always been fragile. And yet, today the system risks collapse, as pushbacks are carried out routinely across the world, including in Europe, in Australia and in the US. How to protect the Geneva refugee convention today?

Essay 2 - The popularity of pushbacks – lessons from Australia

7 June 2021

There is a possibility that the current consensus in Australia – that only pushbacks and the harshest deterrence reduce irregular migration, which is both morally and politically desirable – will be embraced elsewhere, in Asia and in Europe. If this happens refoulement will be normalised around the world.

May hope and effort make 2022 a year of progress towards the goals of humane borders, towards a Europe whole and free, and towards a world in which human dignity is better protected than now.

Until then, the ESI team wishes you, our readers and friends, a happy new year.

Sincere regards,

Gerald Knaus

Twitter: @rumeliobserver

Presenting the ESI proposal at the German embassy in Ankara, 2 November 2015

One of many meetings 2015 and 2016 with Selim Yenel,

Turkish EU ambassador, in Brussels

With Diederik Samsom at the Parliament in The Hague (February 2016)

With the Mayor of Chios in Hamburg City Hall (with Wolfgang Schmidt)