47 again? Russia out, Kosovo in

Dear friends,

It is striking how differently Russia and Kosovo have been treated by the governments of Council of Europe member states in recent years.

Russia, a nuclear superpower with a population of 146 million and a landmass stretching across nine time zones, joined the Council of Europe in 1996. As a Council of Europe member, Russia waged wars in Chechnya (1999-2000), invaded Georgia (2008), annexed Crimea (2014), triggered war in Eastern Ukraine (from 2014), bombed civilians in Syria (from 2015) and then launched an assault against the whole of Ukraine in February 2022.

Kosovo, one of Europe’s smallest democracies with a population of less than 2 million, with a territory that is 0.05 percent that of Russia, declared its independence in February 2008. This was recognised by a large majority of members of the Council of Europe (34 of 46).

International Court of Justice

In October 2008, the General Assembly of the United Nations turned to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague with a simple question: “Is the unilateral declaration of independence by the Provisional Institutions of Self-Government of Kosovo in accordance with international law?” In July 2010, the ICJ concluded that “the declaration of independence of Kosovo adopted on 17 February 2008 did not violate international law”.

Unlike Russia, Kosovo has seen peaceful transfers of political power following free and fair elections. Unlike Russia, independent Kosovo never had political prisoners. Unlike Russia, it has not waged any wars.

And yet, for many years, Kosovo governments have been actively discouraged from applying for Council of Europe membership by other members. The result: Kosovo remains outside. It is today the only European democracy which is not yet a member of the Council of Europe.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine, combined with threats by its leaders against other Council of Europe member states, was finally too much.

On 15 March this year, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted an Opinion. It considered that the Russian Federation can no longer be a member State of the Organisation. The decision was unanimous. That same day, the Russian government announced its withdrawal.

After more than a quarter of a century of being a member, Russia was out. Shortly thereafter, Kosovo’s government announced its intention of applying to take Russia’s place as 47th member. On 12 May, last week, Kosovo’s foreign minister submitted Kosovo’s application in Strasbourg.

What should happen next

What happens next?

If Kosovo is treated like other countries were in the past, the following will happen.

Kosovo’s application is already with the Committee of Ministers, where the representatives of the now 46 member states meet regularly. It should go next to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE).

There in-depth reports are being commissioned, to assess whether Kosovo meets the criteria. Based on these reports, first PACE and then the Committee of Ministers must vote on the application.

The next step is obvious. A vote in the Committee of Ministers is needed at its next meeting to send the application to PACE, where the real work begins.

On 4 May 1992, after the communist dictatorship was overthrown in Tirana, Albania applied to join the Council of Europe. On 21 May 1992, shortly thereafter, the Committee of Ministers asked the Parliamentary Assembly to give an opinion.

On 9 November 2000, after Slobodan Milosevic was overthrown in Belgrade, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia applied to join the Council of Europe. On 22 November 2000, the Committee of Ministers asked the Parliamentary Assembly to give an opinion.

Moving Kosovo’s application from the Committee of Ministers – the 46 governments – to PACE – the members of parliament – should not take long. It should happen on 20 May at the next meeting of foreign ministers of the Committee of Ministers in Turin.

Turin

Italy currently chairs the Committee of Ministers. Luigi di Maio, the Italian foreign minister, has often spoken out in favour of Kosovo’s integration into European institutions.

On a visit to Kosovo in June 2021, Luigi Di Maio stated: “Italy is firmly convinced that Kosovo’s future lies in Europe and we will continue to make our voice heard in Brussels on the various issues on the agenda.”

Many other governments have spoken like this.

On a visit of the Kosovo prime minister to Paris in June 2021, French President Emmanuel Macron stated: “Kosovo, like all the countries of the Western Balkans, has the vocation, when the time comes and when the conditions are fully met, to join the European Union.”

Joining the Council of Europe – and thereby accepting the European Convention on Human Rights – has always been required before joining the European Union.

France should now support PACE assessing whether the conditions for it are met.

On a visit of to Kosovo in March 2022, German foreign minister Annalena Baerbock, praised “the really strong reform orientation” of Kosovo’s new government: “Kosovo has delivered, now the European Union has to deliver.”

Olaf Scholz and Albin Kurti in Berlin

On a visit to Berlin by Kosovo’s prime minister in May 2022, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz praised Kosovo and promised Germany’s support:

“Kosovo took a clear position on all international issues very early on, in coordination with the EU, and is supporting the sanctions against Russia. That deserves great recognition … The Western Balkans belong to Europe. In the future all its countries must also belong to the European Union. This includes Kosovo, of course, whose international recognition Germany has always supported to the best of its ability and continues to support.”

Thus, like Italy and France, Germany should also support that PACE assesses whether the conditions for Kosovo to join Europe’s oldest human rights organisation are met.

Double standards in Strasbourg

It is, however, crucial that the next step is taken in Turin this month at the ministerial session on 20 May.

Ministers only meet once a year. Yes, ministers’ deputies – the ambassadors in Strasbourg – can adopt decisions on all matters at their regular weekly meetings.

But at these meetings any one country can insist that an item should “by reason of its political importance be dealt with by the Committee of Ministers meeting at ministerial level” (Article 2, Rules of Procedure for the meetings of the Ministers’ Deputies).

This means: if no decision is taken at the meeting on 20 May this year, the application can easily be put on ice by a single member state for a whole year.

At the ministerial meeting in Turin, however, forwarding Kosovo’s application to PACE only takes “a two-thirds majority of all the representatives entitled to sit on the Committee” (Article 20 of the statute).

34 of the 46 member states of the Council of Europe have recognised Kosovo’s independence. Others, like Greece, have supported Kosovo joining international institutions even without this.

31 votes are needed in the Committee of Ministers in Turin to send the application to PACE.

The votes are there. The precedents are there. The promises are there. But will it happen?

Did countries like Germany and France mean what they said to Kosovo’s leaders in recent months?

Or will the double standard, which allowed Russia to be a member despite massive human rights violations, but which blocked Kosovo from applying, continue?

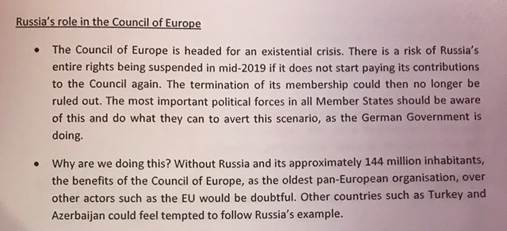

In October 2018, the German foreign ministry sent out an internal note to its diplomats arguing that German embassies should push other countries to make concessions which Putin’s Russia had demanded in return for it once again paying its obligatory contributions to the Council of Europe. The risk of Russia ever leaving the Council of Europe, so the position of the German foreign ministry at the time, was “an existential crisis”:

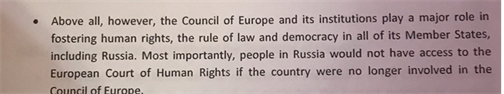

The memo stressed how important it was that Russian citizens kept access to the European Court of Human Rights.

In the case of Kosovo’s recent application, however, a recent internal German memo sent to members of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) in April 2022 suggested that formally Kosovo could not even apply for membership; that it would need to be invited based on a consensus of all members; that such a consensus was inconceivable because of Serbian opposition; and that Kosovo should better be offered – in consultation (“Abstimmung”) with Serbia – alternatives to membership.

One alternative, presented in the April memo, is for Kosovo to be admitted as an associate member “like the Saar.”

This is a remarkable comparison.

Between 1950 and 1957, the Saar was a French protectorate. Pro-German parties (like the CDU) were banned from running in elections. It was never a sovereign state. In 1957, the Saar was absorbed into the Federal Republic of Germany as the Saarland. How can the Saar be a model for a sovereign state?

The paradox is that while some German diplomats in Strasbourg have argued in meetings with other diplomats against Kosovo’s application being treated like that of Albania in 1992 and of Serbia in 2000 in recent weeks, the official position of Germany is that it fully supports Kosovo. Which raises the question: who makes German foreign policy?

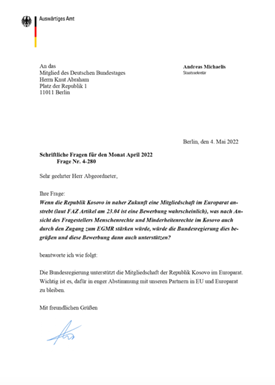

On 4 May, the German government answered a question on this by a German member of PACE: Andreas Michaelis, state secretary in the Foreign Ministry, made clear that “The Federal Government supports the membership of the Republic of Kosovo in the Council of Europe.”

So do most members of the German parliament represented in PACE. There is strong bipartisan support for Kosovo’s application from members of the governing parties and from the main opposition in the Bundestag.

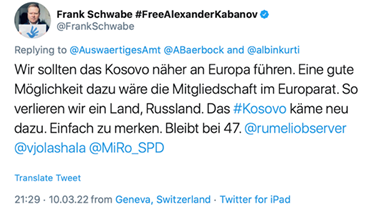

Frank Schwabe of the SPD, who leads the PACE group of Socialists, Democrats and Greens, tweeted:

“We should bring Kosovo closer to Europe. A good possibility would be membership in the Council of Europe. In this way we lose one member, Russia. Kosovo would join. And we remain at 47.”

Knut Abraham of the CDU, member of the foreign affairs and the human rights committees in the Bundestag, asked in a press statement “the federal government to support the membership of Kosovo in the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe”. Konstantin Kuhle of the liberal FDP also endorsed Kosovo’s membership in the Council of Europe as “an important contribution to stability in the Western Balkans.”

Following Kosovo’s application, Germany’s Ambassador to Kosovo tweeted that he was “looking forward to seeing Kosovo as part of the Council of Europe @coe family” and wished “all the best for the membership bid!” Manuel Sarrazin, the German government’s special representative for the countries of the Western Balkans, visited Kosovo’s foreign minister in Pristina and assured her of Germany’s “support for the membership bid!”.

There have been many bizarre arguments made by German and other diplomats in Strasbourg in recent weeks in meetings with their colleagues from other member states:

- Kosovo’s application comes “too early” – this after months of this being discussed by German PACE members.

- Kosovo’s application is too divisive for the Council of Europe – this when members of the Council of Europe have literally been at war with each other in recent years (Russia attacking Georgia and Ukraine, Armenia and Azerbaijan fighting in 2021).

- Kosovo should concentrate on other issues first in its discussions with Serbia – this when Serbia has been a member of the Council of Europe for more than two decades already.

What is needed in Turin is to forward an application to PACE whose goal is to offer human rights protection to all of Kosovo’s citizens, including its minorities.

This is all. However, if even this is not done, what is the point of repeating that Kosovo has a European vocation?

This is, in fact, a moment of truth for many European countries which have long claimed to support Kosovo’s European aspirations. It is also a moment of truth for the Committee of Ministers.

Let European democracies in Turin send a strong signal that the place for European democracies is the Council of Europe. There will never be a better time than now to do so.

With warm wishes,

|

||

|

Gerald Knaus |

Kristof Bender |

Gerald Knaus

“Russia out, Kosovo in?”, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 23 April 2022