Recommendations From Wilton Park Conference, 10 June 2004

- From 2007 onwards, every South East European state that concludes a Stabilisation and Association Agreement should be offered the status of EU candidate, and should have full access to pre-accession programmes, irrespective of whether it meets the criteria to begin full membership negotiations.

- Cohesion should be an explicit objective of EU policy in the whole of South Eastern Europe. SAPARD and ISPA should be continued beyond 2006 and programmes directed at improving the human capital in the region, modelled on EU social fund efforts, should be introduced.

- Assistance levels and funds for the European Union’s South Eastern Enlargement should be sufficient to ensure that the gap between present candidate countries, such as Bulgaria and Romania, and future candidate countries does not grow further. There needs to be adequate provision for a pre-accession strategy in the whole of South Eastern Europe in the financial perspective 2007-2013.

As the political and economic map of South Eastern Europe is redrawn through successive European enlargements, a number of countries of the Western Balkans risk being left on the margins of the new and integrated Europe.

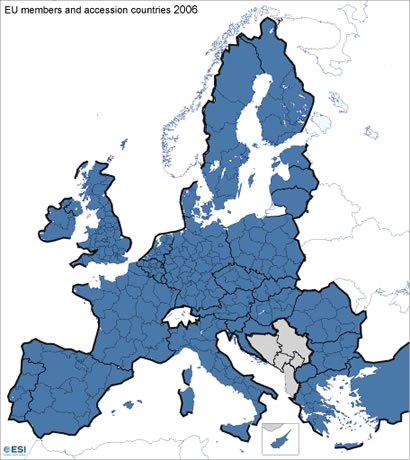

In 1998, the only country in South Eastern Europe which was a member of the European Union was Greece. By 2007, Romania, Bulgaria and possibly Croatia are likely to join, while Macedonia and Turkey are likely to be engaged in membership negotiations. As the experience of the last enlargement has shown, being a full candidate already brings many of the benefits that in previous Mediterranean enlargements only came with membership. Most of these benefits are crucial to potential investors: a stable macroeconomic environment, a predictable regulatory environment, an expectation that every year the physical and administrative infrastructure will improve, access to increased assistance.

At the same time, none of Serbia-Montenegro, Albania or Bosnia-Herzegovina appears likely at this moment to be sitting at the negotiating table with the EU by 2007. It is uncertain whether by that time there will even be ratified SAA agreements between the EU and these countries. There is a risk that, instead of catching up with the rest of the continent, these countries will fall further behind, and the goal of integration – and the promise of regional stabilisation it offers – will become even more distant.

This discussion paper sets out an alternative scenario. The starting point for a new European approach is the reflection on the needs of the Western Balkans which was set out in advance of the 2003 Thessaloniki summit by the Greek EU Presidency:

"As the Western Balkan countries gradually move from stabilisation and reconstruction to association and sustainable development, policies pursuing economic and social cohesion at both national and regional levels become increasingly relevant, in particular having in mind the very high level of unemployment in most of them, as well as the social and regional dimension of ethnic problems. The Greek presidency intends to initiate a reflection on integrating the aim of economic and social cohesion into EU policy towards the region, and on ways and means, including financial, of promoting cohesion through the Stabilisation and Association Process."

There is a need to explore possible ways and means for such a policy. Bosnia-Herzegovina, Albania and Serbia-Montenegro today face very different threats and opportunities from those which existed only three years ago. European policy instruments have not yet adapted sufficiently to meet these new challenges.

There is a pressing need for new strategies to promote structural reform across the region, which is essential to reversing more than two decades of deep economic decline. The European Union, working through the European Commission, needs to enhance its capacity to bring about serious reforms, such as reducing the cost of public administration, liquidating loss-making companies and initiating the retraining of workers left stranded by the collapse of old industrial complexes. There is no need to invent anything new: the instruments that are presently used in a candidate country such as Bulgaria already show the direction in which EU policy should go.

One challenge is to increase the impact of European assistance. Across the region, public administrations steeped in traditions of authoritarian, top-down development policies need to learn new techniques of supporting development under market conditions. They need to be encouraged to mobilise their own limited public resources to support development. They need to develop modern statistical systems to guide their policies, and to build new partnerships between national, regional and local governments. These are precisely the kind of problems which European regional development assistance is designed address. Over the past decades, the European Commission has worked with economically peripheral regions of the European Union, and later with the accession candidate countries, to help them meet these challenges. The instruments and techniques which it has developed are directly relevant to the Western Balkans.

The Thessaloniki Summit in June 2003 offered a real opportunity to redefine the nature of the European engagement in the Western Balkans. It did not succeed in this, but it did accelerate a positive process that led to the most recent (positive) Commission avis on Croatia and the Macedonian application.

In the coming two years, the success of a European policy towards SEE should be measured by the following benchmarks.

- From 2007 onwards, every South East European state that concludes a Stabilisation and Association Agreement should be offered the status of EU candidate, and should have full access to pre-accession programmes, irrespective of whether it meets the criteria to begin full membership negotiations.

There should be a pledge by the EU to treat all countries from the Western Balkans which have signed SAA agreements as official candidates, with access to all pre-accession instruments. This should be divorced from the question of whether a country is already able to negotiate full membership, just as was done in the case of Turkey at the Helsinki summit in 1999.

- Cohesion should be an explicit objective of EU policy in the whole of South Eastern Europe. SAPARD and ISPA should be continued beyond 2006 and programmes directed at improving the human capital in the region, modelled on EU social fund efforts, should be introduced.

This means that the EU makes a serious commitment to preventing all of the countries of the Western Balkans from falling behind the wider region, and helping them to reach a level of development where formal accession becomes a real possibility. Cohesion is not an objective of the EU in the wider Europe or the rest of the world, but a specific aspect of EU integration. It requires a more significant commitment of resources and more intensive involvement by European institutions.

In return, it offers the EU significantly more leverage to bring about real change in the region. It would place the EU in a much stronger position to demand a credible commitment to the other pillars of EU policy: responsible fiscal policies and an open trade environment. Most countries of the region have already succeeded in reducing inflation. Some already use the Euro as official tender or have introduced currency boards. Across the region, bilateral free-trade agreements are reducing trade barriers every year. By making a pledge to support cohesion on a regional basis, the EU would be in a strong position to demand continuing and coordinated efforts along these lines.

In order that future European funds are used more effectively, the EU should begin to employ new assistance strategies, applying the experiences gained from cohesion policy elsewhere in Europe as to how to mobilise domestic resources, build domestic governance capacity and encourage the emergence of regional development policies.

The Commission should undertake to examine how lessons from the cohesion funds can be applied in the Western Balkans, including co-financing, conditionality, regional development planning and partnership between the Commission and national and regional governments.

- Assistance levels and funds for the European Union’s South Eastern Enlargement should be sufficient to ensure that the gap between present candidate countries, such as Bulgaria and Romania, and other countries of South Eastern Europe does not grow further. There need to be adequate provision for a pre-accession strategy in the whole of South Eastern Europe in the financial perspective 2007-2013.

Making a serious commitment to cohesion in the Western Balkans is more about developing new assistance strategies than about mobilising large new financial resources. However, the gap in the resources envisaged beyond 2004 between Romania and Serbia, or between Bulgaria and Macedonia, raises obvious questions as to the credibility of the European commitment to the region.

In 2006, the European Union promises to spend €1.432 billion to help Bulgaria and Romania prepare for accession and catch up with the rest of the continent. This is equivalent to 2.6 percent of the combined GDP of these two countries. At present, the European Union intends to allocate no more than €570 million in total assistance to the countries of the Western Balkans – equivalent to slightly more than 1 percent of their GDP.

Narrowing the gap between the new member countries, the candidate states Bulgaria and Romania and the Western Balkans SAP countries would not involve a major new commitment of EU resources – particularly if existing, resource-intensive post-war missions are phased out in favour of a Commission-led Europeanisation process.