A monastery, Kosovo courts and the road to the Council of Europe

- Res judicata

- The Council of Europe and the Decani land

- The only way forward – implementation

- Sincere collaboration

Dear friends of ESI,

Last week, an ESI team travelled to Kosovo to examine how the only European democracy that is not yet a member of the Council of Europe might join it this year. And how to address an urgent issue, unresolved for far too long, that has become central to this goal. You find our conclusions in a new ESI publication:

Memo on Decani

The rule of law, an urgent issue and Kosovo in the Council of Europe

4 March 2024

The monastery of Visoki Decani, Kosovo, March 2024

The issue: a property dispute in the municipality of Decan, involving the most famous Serb Orthodox monastery in the Balkans (Visoki Decani). The bigger question: how does the rule of law and the implementation of judgements in Kosovo function today? The high stakes: by solving this, Kosovo opens the door to joining the Council of Europe, the leading European institution for human rights protection. Settling this now – with time running out – would be:

- a win for the rule of law and for all citizens of Kosovo, who would also benefit from the human rights protection system of the Council of Europe.

- a win for the monastery of Visoki Decani and the Serb minority in Kosovo.

- a win for the Council of Europe, in particular for its Parliamentary Assembly (PACE), whose rapporteurs have made this a central focus.

In order to understand what is at stake, and what progress is possible, our Memo on Decani looks at four issues:

The dispute: why this legal battle about just 24 hectares of land matters so much.

History and politics: why this has proven so hard to resolve until now.

The solution: why there is only one way to resolve this.

The lesson: how this shows the importance of Kosovo becoming a member of the Council of Europe.

Mysterious 14th century fresco in Decani – map of the region

Res judicata

Res judicata (Latin): a matter that has been adjudicated by a competent court and therefore may not be pursued further by the same parties.

The monastery of Visoki Decani (High Decani) was built in the 14th century by one of the most important medieval Serbian kings, Stefan Decanski, who called on Franciscan builders from the Adriatic coast to build his church. It has been recognized in 2004 by UNESCO as part of world heritage.

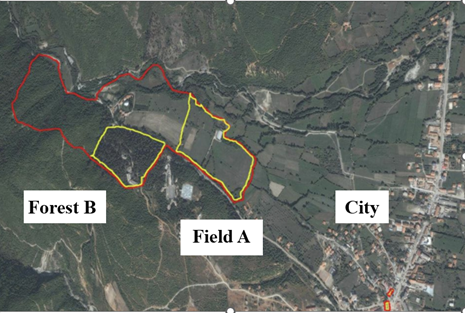

To understand how Decani monastery became embroiled in a decades-long dispute over land, and why this concerns Kosovo’s Council of Europe accession, let’s begin with a map.

The map shows the small city of Decan/Decani (Albanian/Serbian) to the right. West of Decan, high mountains separate Kosovo from Montenegro and Albania.

- The red line shows land that the monastery considers its property, surrounding its church and main buildings.

- Within the red line, yellow lines mark two pieces of land which are disputed. One is a field (A). The other is a forest (B). These add up to 24 ha.

Much of this land has been registered for a long time in the cadaster as belonging to the Decani Monastery. But 24 parcels – those comprising field A and forest B, as well as four small parcels of land in the middle of Decan city – were only registered in the cadaster in the name of the monastery in early 1998, following a donation by the Serbian state in late 1997.

Following the end of the war with NATO in June 1999, the Serbian state withdrew its police, military and most of its institutions from Kosovo. UNMIK, an international UN-administration, was established to govern Kosovo for an interim period.

In 2000, a legal dispute erupted in Decan over the 24 parcels. Workers and managers who claimed to represent two socially owned enterprises in Decan now argued that these parcels should be returned to them. In June 2002, a municipal court in Decani ruled that the Serbian state’s gift of 24 parcels to the monastery had been a violation of property rights. It ordered the re-registering these parcels in the cadaster in the name of the socially-owned enterprises.

This was done. It was the beginning of a long legal battle. In 2005, a district court quashed the 2002 judgement of the municipal court on formal grounds. In May 2008, an UNMIK executive decision stated that Decani monastery would continue to enjoy “undisturbed possession” of these 24 parcels and that these should be reentered into the cadaster in the name of the monastery. The cadaster remained uncorrected.

Abbot of Decani, Father Sava, in the monastery’s library

In May 2009, UNMIK, in charge of all socially-owned enterprises and their property, proposed in the Kosovo Supreme Court a settlement to Decani monastery. The settlement idea: UNMIK would transfer 20 of these 24 contested parcels of land back to the monastery (field A and forest B). The monastery would waive its rights to the four parcels in the city of Decan.

Kosovo Supreme Court and Constitutional Court

But did UNMIK have the right to conclude such a settlement with the monastery? Between 2009 and 2016, this issue was adjudicated in the Kosovo Supreme Court and in the Kosovo Constitutional Court, with a clear result:

- In March 2009, the Kosovo Supreme Court ruled that UNMIK/KTA had “the sole right to represent the interests of the [socially-owned] enterprises.”

- In July 2010, the appeals panel of the Kosovo Supreme Court reaffirmed that UNMIK/KTA had “the sole legal standing” in this matter.

- In December 2011, the Supreme Court declared once more that the decision on the legal standing of UNMIK/KTA was “final and therefore binding and not questionable anymore.” It stressed that this should be considered res judicata, binding on all parties and on all courts.

- On 27 December 2012, the Supreme Court ruled once more that this issue had now been settled and could no longer be challenged. Predictability and legal certainty required that final judgments were no longer challenged, no matter whether “they are correct or not.”

And yet, throughout the following twelve years, nothing was done to implement these decisions. Finally, the matter reached the Kosovo Constitutional Court, which was now called upon to settle the issue in 2016.

The Constitutional Court’s ruling was unambiguous:

“The right to a fair trial under Article 6 of the ECHR and Article 31 of the Constitution includes the principle of legal certainty, which encompasses the principle that final judicial decisions which have become res judicata must be respected and cannot be reopened or become subject to appeals.”

It reaffirmed that the Supreme Court’s December 2012 decision was “final and binding and as such as res judicata.” There was no longer any possible judicial challenge to it. It simply had to be implemented. This was eight years ago. The cadastral records remain unchanged.

The Council of Europe and the Decani land

Few other issues have been discussed in Kosovo’s courts as often as the 24 parcels of land surrounding Decani monastery. It is not surprising, therefore, that in 2023 all rapporteurs and legal experts asked by the Council of Europe to assess the preparedness of Kosovo to join the organization have focused on this matter. And all asked the same question: when will these judgements be implemented?

The heart of this case is the issue of legal certainty. As the Constitutional Court reminded everyone in its 2016 judgement, the rule of law “would be illusory, if the Kosovo legal system allowed a final, binding judicial decision to remain inoperative to the detriment of one party.” It restated this in one of its regular review sessions on the implementation of judgements in September 2021:

“The Constitutional Court reiterates that the enforcement of its decisions is an obligation for all persons and institutions of the Republic of Kosovo pursuant to article 116 of the Constitution. Furthermore, the enforcement of final decisions is a fundamental principle of the rule of law …”

ESI’s Kristof with deputy foreign minister Kreshnik Ahmeti (Pristina)

The only way forward – implementation

All this leaves only one way to address this issue: the government of Kosovo must ensure, with all the instruments and the authority at its disposal, that the judgements of 2012 and 2016 are immediately implemented so that the Kosovo Cadastral Agency (KCA) changes the entries in its records, with a few computer clicks, and grants the ownership of the 20 parcels of land to the monastery in line with the settlement with UNMIK.

The KCA, like any public administration, is under the legal obligation to implement court decisions without delay in any case. It is an executive agency under the control of the government. Not implementing final and binding court judgements is unacceptable.

This should never be dependent on what any other actors do or do not do. And yet, there is one additional reason for the Kosovo government to act on this today, and to resolve something all previous governments have failed to resolve. This issue has recently become a conditio sine qua non for Kosovo to advance on the path to Council of Europe membership.

Kosovo applied for Council of Europe membership in May 2022. ESI wrote about it at the time:

47 again? Russia out, Kosovo in

Support Kosovo’s membership in the Council of Europe

The Committee of Ministers referred the application to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) in April 2023. PACE asked “eminent lawyers” to produce an in-depth report on the candidate, which in this case was published in November 2023:

Report of the eminent lawyers on Kosovo

This report notes that Kosovo has a “functioning parliamentary system”, its government is “determined to fight corruption” and there are “strong guarantees for independence of the judiciary.” It also stresses that the Decan land issue and the non-implementation of court decisions in this case is an issue of major concern, highlighting:

“The [Constitutional] Court decided that 24 hectares of disputed land belonged to the Visoki Decani Monastery. This judgment was criticised by politicians and, despite repeated appeals by the International Community, not implemented. This is a clear violation of the rule of law. The Kosovo authorities should implement without further delay the judgment of the Constitutional Court in the Visoki Decani case.”

Similar messages have come from the three rapporteurs appointed by PACE, members of parliament from Greece, Sweden and Monaco. In fact, the consensus on this in PACE is overwhelming.

Dora Bakoyannis (Greece) – Azadeh Rojhan (Sweden) – Béatrice Fresko-Rolfo (Monaco)

Three PACE rapporteurs on Kosovo membership

Thus, the issue of the 24 hectares of land in the municipality of Decan risks turning into an insurmountable obstacle to a positive assessment by PACE. At the same time, it is an obstacle that could be overcome fast. The legal situation is clear. What needs to be done is clear. So is the political case for it.

Land already farmed by Decani monastery – the forest

Let us revisit the 24 ha of land that this is all about. The farmland is already used by the monastery, and has been used for decades. What is needed here is the administrative recognition of a legal and practical reality. The same is true for the plots in the forest (B). There are two ruins in the forest. As it lies within the Special Protective Zone it is closed to any development that puts at risk “the monastic way of life.”

Sincere collaboration

To join the Council of Europe, members need to make a commitment:

“Every member of the Council of Europe must accept the principles of the rule of law and the enjoyment by all persons within its jurisdiction of human rights and fundamental freedoms, and collaborate sincerely and effectively in the realization of the aim of the Council.”

(Article 3, Statute of the Council of Europe adopted in 1949).

The role of the Council of Europe is to help democratic government do what they should do in any case: respect the European Convention on Human Rights. This is what Kosovo is asked to do here, too.

All of this is an internal matter for Kosovo. Decani is a monastery in Kosovo. The Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court are Kosovo state institutions. Implementing their judgements is a matter of principle for anyone who respects the Kosovo constitution. This is not a concession or something to bargain over. It should be backed by a broad consensus in Kosovo as it is most of all in the interest of all citizens of Kosovo. And in their interest, the time has come for a win-win-win for Pristina, Decani and Strasbourg.

Yours sincerely,

Gerald Knaus