On April 16 the Dutch daily paper De Volkskrant published a long article on the genesis of the EU-Turkey agreement, as seen from The Hague and Brussels. If you are interested, here is an unofficial translation.

Volkskrant, 16 April 2016

The Deal

– unofficial translation by ESI –

A mysterious word, deadlines, heated arguments, secret meetings and Turkish pizzas at midnight. The EU-Turkey refugee deal was hard-fought, with Prime Minister Rutte on the frontline. “Hand in hand jumping off the cliff.” A reconstruction.

By Marc Peeperkorn

It is already dark on Friday, 18 March, when Prime Minister Mark Rutte leaves a meeting in the colossal Brussels Justus Lipsius building. For two days, he has cautiously negotiated with his EU colleagues to win a pioneering refugee agreement with Turkey. In an agreement where Dutch influence weighs heavily, Rutte plays a leading role in front of and behind the scenes. “Do you realize that in three months’ time we have fundamentally changed the European asylum policy?” says an aide accompanying the Prime Minister to his car. Rutte looks at him grinning: “Well done!” Energetically he steps into the grey-brown BMW, on his way to The Hague.

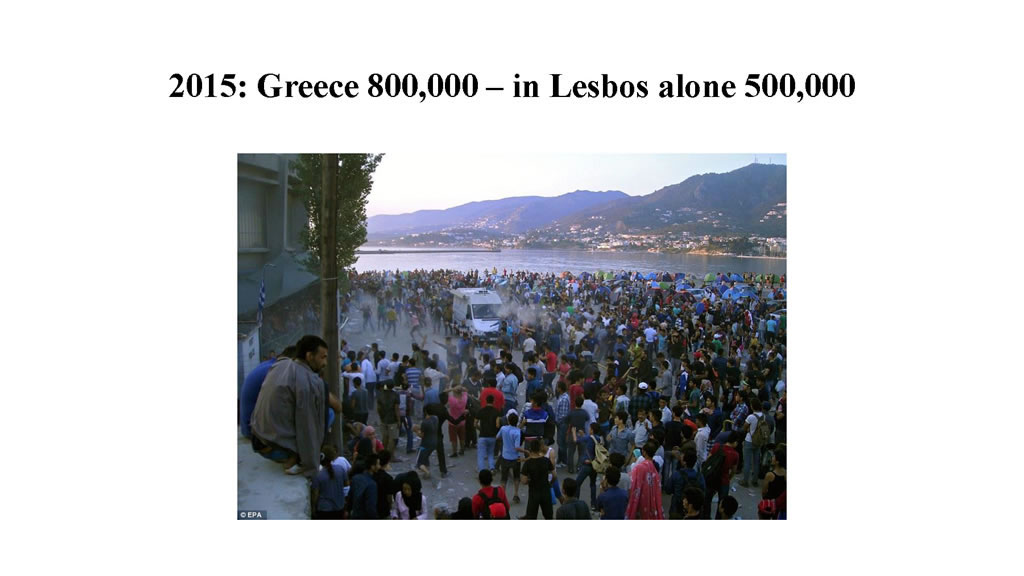

This is a revolutionary deal, both supporters and opponents acknowledge this. It was born out of hard political and humanitarian realities: 2016 could and should not be a repetition of the traumatic 2015. Another 850 thousand refugees transiting through the Greek islands to the rest of Europe; again many hundreds of men, women and children drowning in the short stretch of a few nautical miles between Turkey and the islands; even more border controls, fences, protests and tent camps: leaders cannot deal with all of this. Let alone their parliaments, their voters and the EU.

What will cause problems eventually are Europe’s open borders and the lip service that member states pay to the already feeble return schemes for migrants from distant countries. The Turkey-EU action plan to stem the flow of refugees, agreed at end of November was filled with intentions that brought no results. “The migrants knew: today in Lesvos, tomorrow in Berlin,” as an EU official described the chaos at the end of the year.

THE STRATEGY

One word: “Readmission”. Rutte’s role in the agreement likely starts changing on Thursday, 17 December 2015. European leaders are, again, in the Justus Lipsius building and discuss again the migration crisis. Just before dinner they put the finishing touches to the final declaration. “I want only one word to be added to the text,” says Rutte. His colleagues are relieved, as Rutte is known to check the final conclusions line by line. Thus the word “readmission” lands in the text: not deportation, return or other non-binding terms, but a term that means: migrants who are not entitled to asylum must be “taken back”.

The Dutch delegation’s chamber gives out a suppressed cheer. “The hook that we wanted was put in the wall,” says one person involved. “The rest of the leaders didn’t notice anything. Our action was totally under the radar, also for Angela Merkel.”

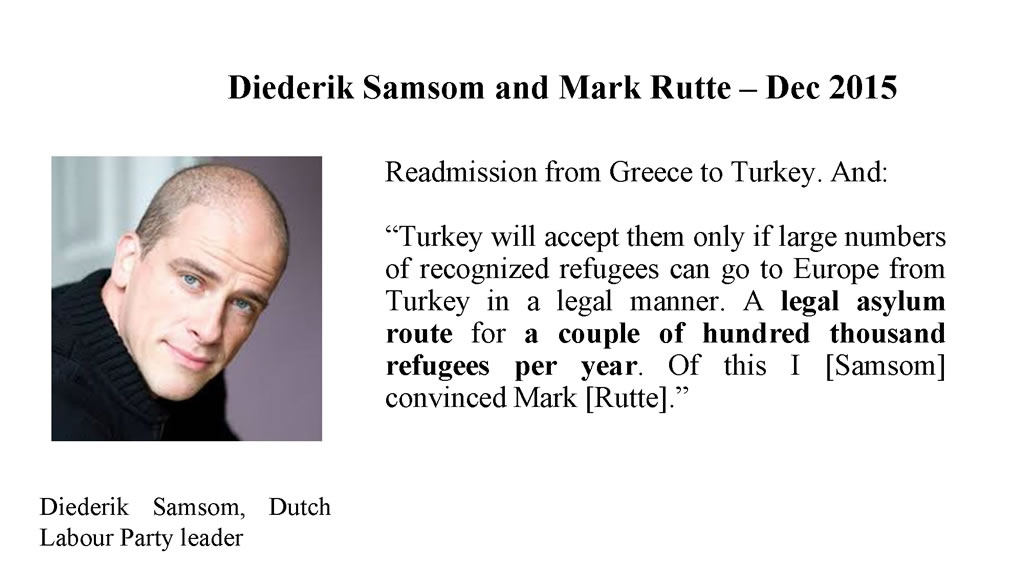

That Rutte was prepared is due to PvdA leader Diederik Samsom. At the beginning of December he visited the Turkish town of Izmir, where in the markets and squares human smugglers meet their desperate customers, without much publicity. Overnight Samsom drove with a police patrol to the coastal town of Cesme and saw “two front crawl strokes away” the lights of the Greek island of Chios. Samsom understood: if the refugee stream was to be reduced “to zero”, as his coalition partner Rutte wanted, then a taboo-breaking approach was needed.

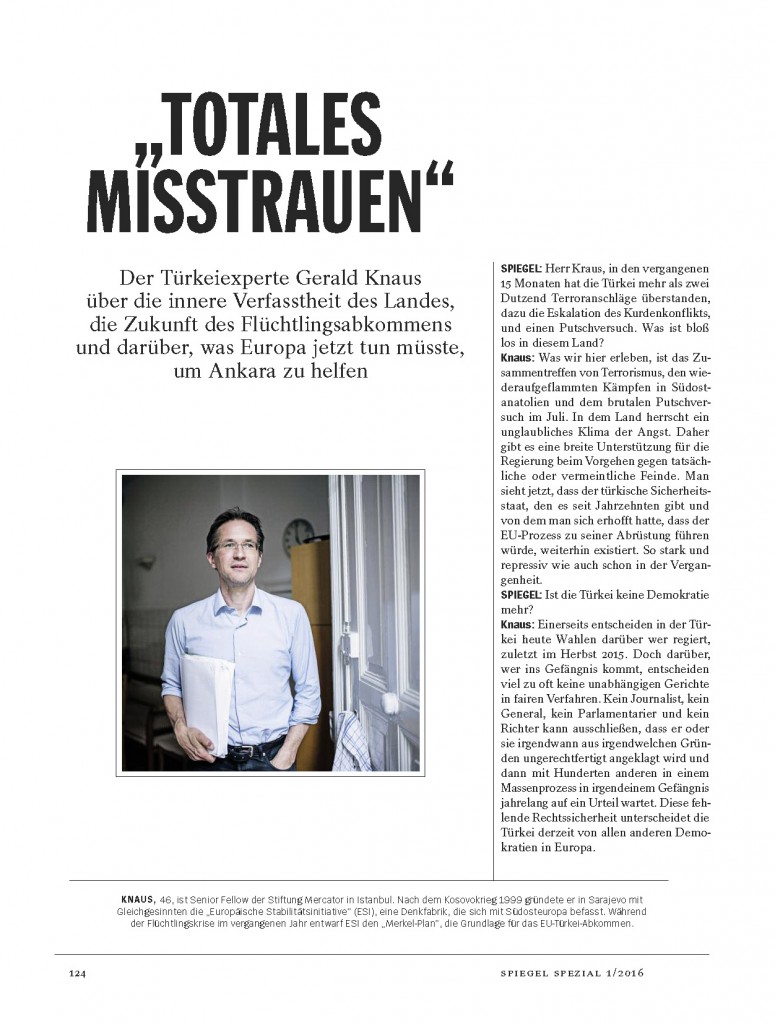

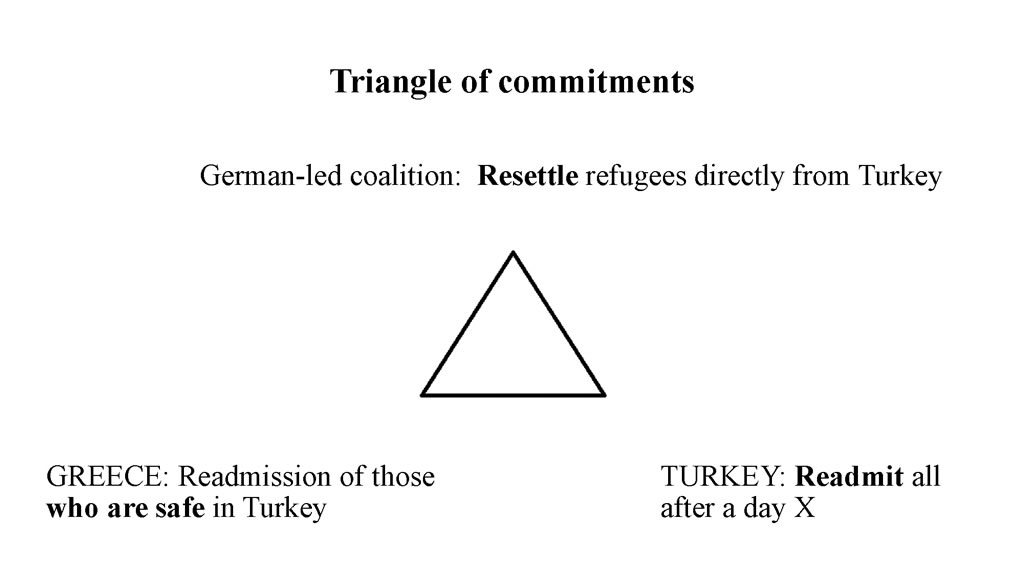

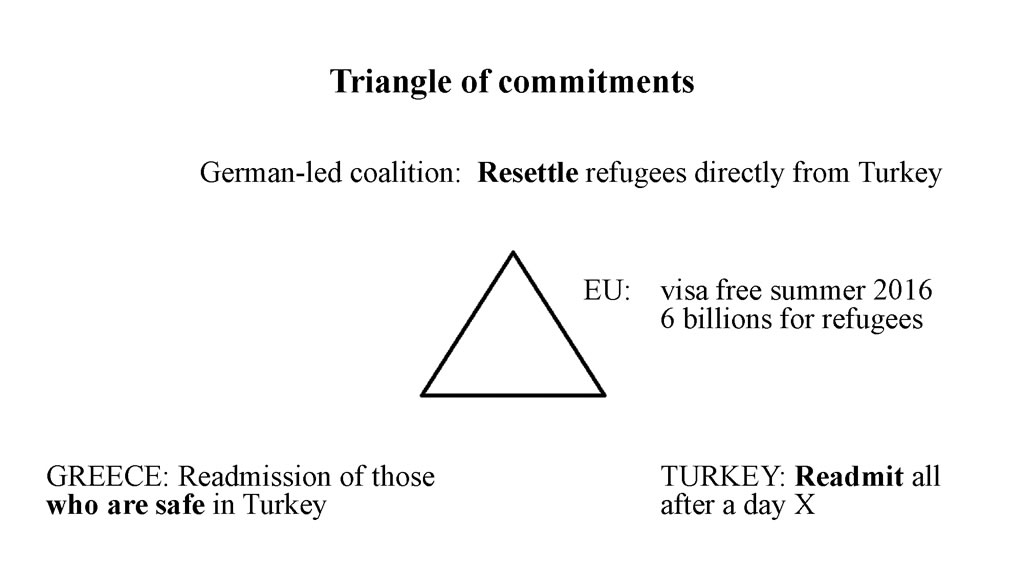

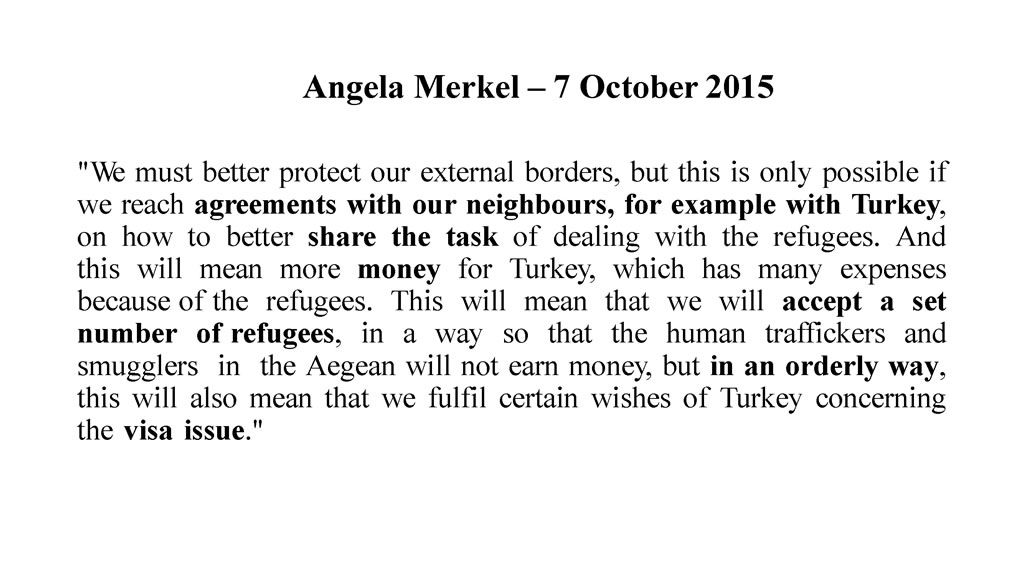

Samsom was inspired by some “reading material” that he received from the Dutch Embassy in Ankara, in preparation for his visit. In that folder was the plan of Gerald Knaus, chairman of the European Stability Initiative, a European think tank. Knaus spoke wishfully of a Merkel plan, hoping that the Chancellor would pick up on it. Later, Rutte turns it into a Samsom plan: return all migrants to Turkey by ferry in exchange for a legitimate air bridge to Europe for recognized refugees.

On Monday, 14 December, the weekly discussions of the governing coalition are held in The Hague, with Samsom and Lodewijk Asscher for the PvdA, Rutte and Halbe Zijlstra for the VVD. Samsom talks about his visit and ideas and finds a surprising amount of understanding from the two liberals. They see similarities especially with the government’s previous letter on asylum policy and the VVD’s asylum plan by Malik Azmani, a deputy.

Three days later, prior to the EU summit, Rutte consults with the so-called coalition of the willing in Brussels. It is made up of about a dozen countries who want to make progress with the Turkish agreements. Rutte has the core of the Samsom plan sketched out on a piece of paper. He consults with Merkel who has been pressing for more generosity on legal migration from Turkey. Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, also present, is startled: why take back all the refugees? A few hours later Rutte nails the take back hook in Brussels on the wall.

On Friday, 1 January, the Dutch EU presidency begins. Ministers and officials have been cramming gorgeous policy programs for eighteen months, but everyone knows: The Netherlands will be judged on managing the refugee crisis. For the VVD, the Presidency is not a burden that they cannot avoid anymore; Rutte, but also State Secretary Klaas Dijkhoff (Security and Justice), are highly motivated.

Therefore, on Thursday, 14 January, Dijkhoff invites, in secret, the Greek Minister for Migration, Ioannis Mouzalas. They have lunch at the ministry in The Hague; fish with salad and sparkling water. Dijkhoff makes it clear that Greece may soon need to return all migrants, including Syrian refugees, to its archenemy Turkey. Mouzalas swallows, his leftist Syriza government abhors evictions, but finally nods.

Friday, 15 January, Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission, uses his comeback in the New Year for a political thunder speech. The euro, the single market, Schengen, everything will disappear if the flow of refugees will not be brought under control, Juncker warns.

A week later, Wednesday, 20 January, Prime Minister Rutte seizes the political launch of the EU Presidency by drawing a hard deadline. “The number of refugees must drastically go down in the next six to eight weeks,” he says in the European Parliament. A day earlier EU President Donald Tusk gave the Union two months. There is no way that they co-ordinated their statements, but both politicians share the feeling that something horrible is about to happen.

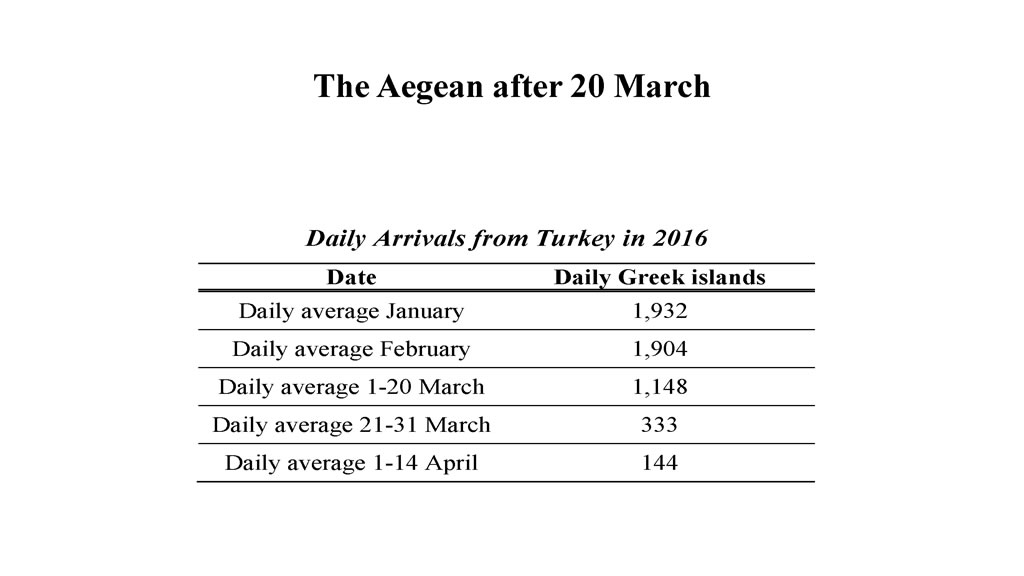

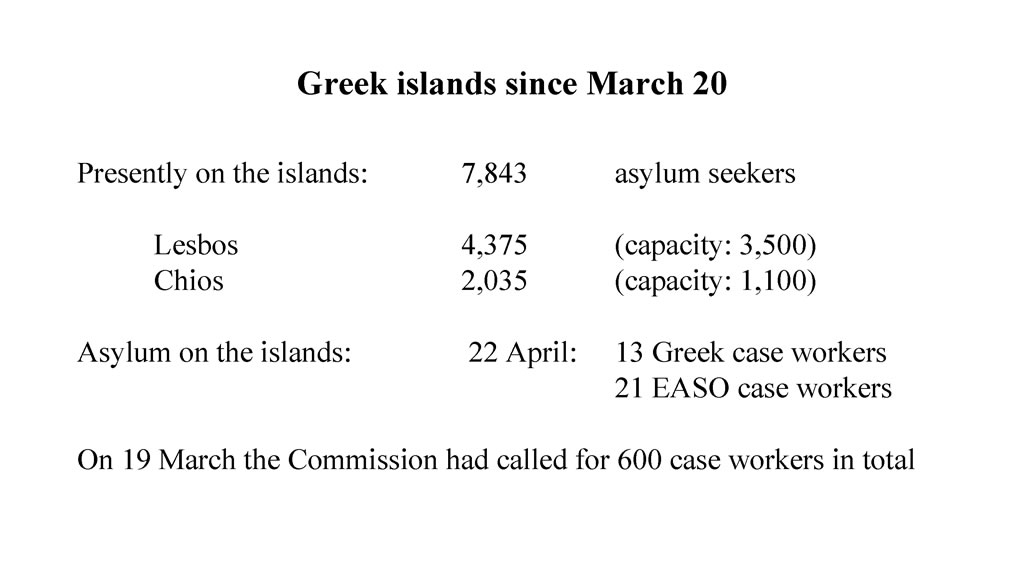

“We didn’t know what to do anymore” admits a Dutch official. It was not the Turkey action plan that determined the refugee stream, but the weather. An employee of Tusk holds up two iPads: on the one a graph with the wind force and direction of the Aegean Sea, on the other the number of refugees in the Greek islands. “The correlation was striking,” says the employee. Sometimes there are 4,000 immigrants per day, and that in January. “The sailing season had not even started yet,” says an EU official. “It was now all hands on deck: Help! Spring is coming!” Brussels fears in 2016 not one but two million applications for asylum.

Thursday, 21 January, the political and economic elite meets in Davos (World Economic Forum). Rutte is there, as is Davutoglu. Rutte makes his major concerns known to the Turkish Prime Minister. To draw a deadline for the action, Rutte suggests to put together a team of senior officials: two from the Netherlands, two from Germany, two from the Commission and some more from Turkey. Their task is pulling and dragging, to continue pushing when the leaders are home again. The company was named the “Ankara club” by the prime minister. It will be as important for the final deal as the politicians.

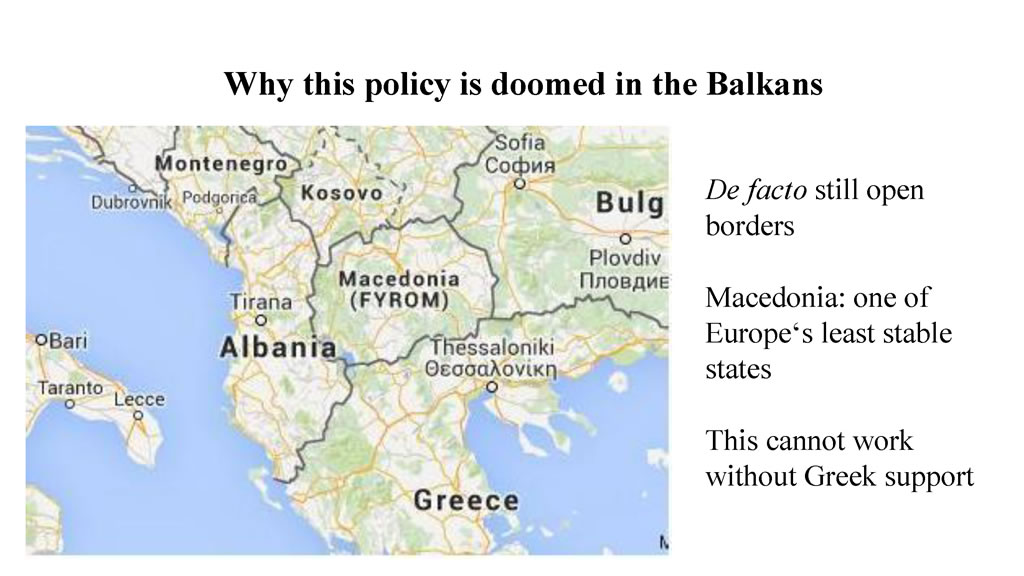

Crucial is also the letter that Juncker writes on Monday, 25 January, to the Slovenian Prime Minister Miro Cerar. Very straightforwardly the President announces that Member States and non-EU countries (Macedonia) may close their borders to immigrants who want to travel alone (to Germany) or who have no chance of obtaining a residence permit (economic migrants). In short: Greece may be sealed off.

“A turning point,” says a diplomat who did not forget how shortly before, Juncker was very critical of border controls. An EU official calls the letter the “Genesis of the solution to the problem of asylum”. Both speak of “cascading back”, allowing back flow of refugees to Greece and finally Turkey. Half a month later the closing of the Balkan route seems to be an effective means of pressure against Turkey.

Without explicitly naming the letter (which was never published) State Secretary Dijkhoff uses it as a crowbar at a meeting of European justice ministers on the same day in Amsterdam. Macedonia receives support for guarding its borders. The Greek minister Mouzalas responds bitterly. For dinner Dijkhoff has invited the Turkish Minister of the Interior Sebahattin Öztürk, and there he is informed of the Balkan dam raised by Europe.

THE BLUNDER

Germany furious about Samsom’s bad timing

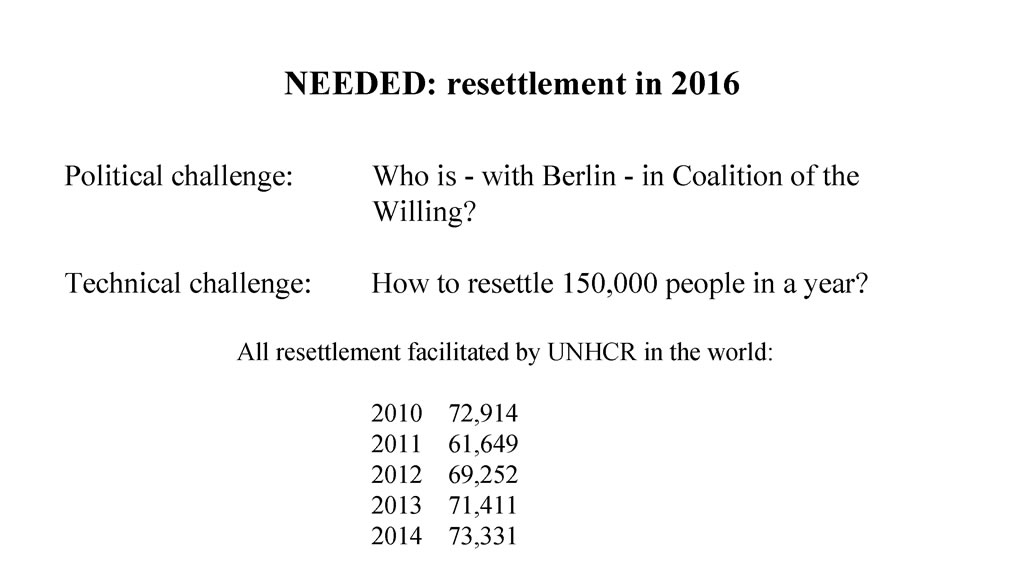

Thursday, 28 January, Labour leader Samsom gives, through an interview with the Volkskrant, a glimpse of what is going on behind the scenes. He talks about the Ankara club and outlines the main features of the new agreement with Turkey which is being changed frantically: the returns by ferry and airlift for 150 to 250 thousand legal immigrants per year. In the afternoon, an employee of Rutte receives a text message from his German colleague: “What a terrible way to kill a good plan.”

Berlin fears that Davutoglu will back out. Turkey is home to 2.7 million refugees and the last thing that Davutoglu is expecting is the message from the Netherlands that there is still more to come. “It could not have come at a worse time,” says an official. Samsom admits later that the interview was “barely consulted” with Rutte. Or even with his own group. The effect is that the Samsom plan gets international attention. “It got fixated in the minds of European leaders,” says a diplomat.

On Sunday, 31 January, officials of Security and Justice, Foreign Affairs and General Affairs write their own action plan. It is named “Reducing the flows” in English because it was used as a guide to the Ankara club. The idea is simple: if from mid-March the refugee stream needs to be dramatically reduced, which measures are needed to achieve this? A division of work and labour is created: what will Rutte do, what will Merkel. “You should always prepare for the next question of your political boss”, a person explains the dynamic action plan.

On Thursday, 4 February, all the political protagonists are in London for the big Syria donor conference. On the margins of it, Merkel, Rutte, Tusk, Davutoglu and Austrian Chancellor Werner Faymann meet. The Turkish prime minister admits the failure of the old agreement from November. We need something new, something better.

Merkel is politically under increasing pressure domestically due to the massive influx of asylum seekers. The chancellor visits, in view of elections in three federals states (13 March), Davutoglu in Ankara on Monday, 8 February. The result is modest: a list of promises about cooperation and a joint request to NATO to deploy boats in the Turkish-Greek waters against smugglers.

Two days later (Wednesday, 10 February) Davutoglu comes to The Hague. He elaborately consults Rutte on how to break the deadlock. Davutoglu makes clear that he does not want to dry up the flow of refugees first and only then – perhaps, one day – to be released via a migration air bridge to Europe. “Immediate crossing”, is the message. This time it is Rutte swallowing, because he is the man of the “first to zero”.

“All the wheels had to turn at the same time,” an official characterizes the Turkish desire. A colleague has a more dramatic metaphor: “Hand in hand jumping off the cliff.”

The conversation goes on in a good atmosphere. Davutoglu appreciates the directness of Rutte. Hard but fair, he says. He calls to settle the refugee issue under the Dutch EU Presidency. Davutoglu has little confidence in the upcoming Slovak presidency – Slovakia refuses to accept any asylum seekers.

In the evening, Rutte is the main guest at the first Correspondents’ Dinner in Amsterdam. It is intended that, just as in the US, the prime minister, other politicians and commentators make fun of each other once a year. “If that fails, I’ll just call it the Samsom Plan,” Rutte jokingly says.

Thursday, 18 February, and Friday, 19 February, the EU leaders wait for another difficult summit: the one about Brexit. Tusk has worked for months on a compromise that Britain must remain in the EU and does not plan to disrupt his “party” with a headache from another file: migration. “Tusk wanted to show: the EU is capable of solving a large and complex problem. But not two at once,” says an EU official.

But he does not count on Merkel and Rutte. The chancellor lets Tusk know in advance that she has “complete confidence” in his Brexit approach and wants to talk especially about migration. Tusk yields. The dinner of the leaders Thursday evening is reserved for migration. Ultimately the discussion does not really work out, because Davutoglu does not come to Brussels due to the attacks in Ankara. Nevertheless, for the first time the leaders discuss Turkey’s “one-for-one”-wish. At Merkel’s request, an additional EU-Turkey summit is held on 7 March. She wants a breakthrough before the federal state elections of 13 March.

On Thursday, 3 March, Samsom airs his frustration in the Volkskrant. The PvdA fears that the momentum has evaporated for his plan because the EU and Turkey are waiting for each other. As a sign of “good will” the EU should take already at least 400 refugees per day from Turkey. Zijlstra immediately strikes the idea down: “First the zero, then the exchange, otherwise we are doubly screwed,” says Zijlstra.

The piece from de Volkskrant leads to a roaring argument between Samsom and Rutte. On the phone, the prime minister accuses his coalition partner that his timing is (again) disastrous. Ankara doesn’t do anything with the goodwill gesture, says Rutte. Wait and pull is his motto. Emotions are running high. “Screw it then!” Samson shouts through his mobile phone to Rutte. Before he hangs up, he calls on the prime minister to take the offer, if the Turks come up with one. The quarrel between Samson and Rutte is settled again quickly. The two call each other for weeks “almost every fifteen minutes”, says an official.

That Samsom says this just that Thursday is no coincidence. He knows – from Gerald Knaus of the European Stability Initiative – that Ankara wants to move. Knaus, the man of the Merkel/Samsom Plan, has excellent contacts in Ankara, Berlin and Brussels. Tusk and European Commissioner Frans Timmermans also visit the Turkish Prime Minister in Ankara that afternoon. A little pressure won’t hurt, Samsom says.

Davutoglu makes an interesting offer to Tusk and Timmermans: he is willing to take back all economic migrants who arrive via Turkey into Greece. That would nearly halve the flow of refugees. The news gets a prominent place the next day. When Tusk and Timmermans ask if there is anything more to get, they get no for an answer.

The Ankara club also dines in Ankara that evening. There the atmosphere is quite different: the Turkish officials seem indeed willing to discuss matters further. Taking back Syrian refugees is explicitly discussed. “We will come up with a new proposal soon,” the Turks promise. Late in the evening Rutte receives a text message from one of his officials: the door with the Turks is opening, definitely try to get more.

THE BREAKTHROUGH

Turkish pizza for Merkel and Rutte

Sunday midday on 6 March the EU ambassadors in Brussels go once again through the final declaration for the EU-Turkey summit the following day. Everything is in it: Turkey takes the economic migrants back, the NATO mission in the Aegean can begin. Around 5 o’clock everyone goes home happy. “Prepared according to the handbook,” says an EU official about the summit on Monday.

The Dutch EU Ambassador Pieter de Gooijer and his German counterpart, however, do not go home. Another meeting awaits them, one that will put everything upside down.

Davutoglu has invited Merkel for coffee Sunday evening at the Turkish EU embassy in Brussels, Avenue des Arts. Merkel asks whether Rutte will come along, after all he is EU president and the two are pulling together for weeks now on the refugee crisis. Some Dutch officials mix up their names to “Ruttel and Merke”, so close is the bond.

The expectations on the Dutch side are low. “Relationship management” is what Rutte is told to do during coffee with Davutoglu; especially hold him to what is included in the draft final declaration. Rutte and Merkel come with small delegations, five men, the Turks welcome them with about 40 employees. “It was a bazaar,” recalls one participant. “Everyone ran into each other. I soon dropped our idea of a short session in a small context.” When Davutoglu arrives a little after 21 o’clock – he comes with some delay from Tehran – he immediately proposes a conversation just among the leaders.

The Dutch and German officials withdraw. Ambassador De Gooijer ends up by chance in the Turkish delegation room. “It is taking a long time”, he says after 20 minutes to the Turkish Ministers of Foreign and European Affairs. “More will come”, they answer. What then?, de Gooijer asks carefully. “Syrians” is the answer. “Take them back.” Then the ministers keep their mouth shut.

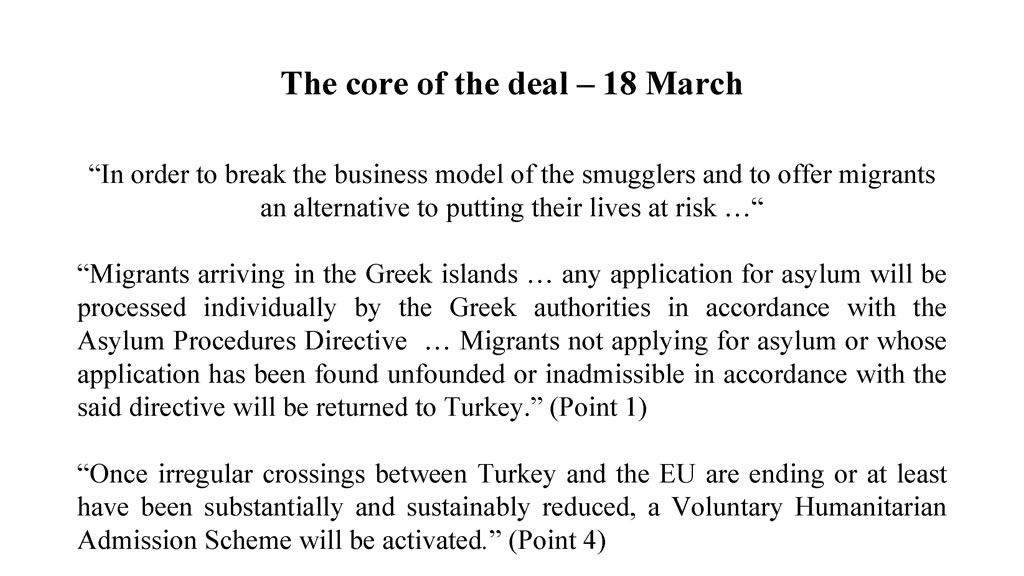

In the large meeting room on the street side, Davutoglu submits a paper for Merkel and Rutte: one page with twelve points, five for Turkey, seven for the EU. It is stated in clumsy English. The last changes were made during the flight from Tehran, then it had to be printed, which was not possible on the plane. Davutoglu offers to take back all refugees, exactly what Merkel, Rutte and the Ankara club want. But it has a hefty price: instantly 6 billion for the reception of refugees; for every Syrian Turkey takes back from Greece, Europe resettles one from Turkey; on 1 June lifting of visa requirements for Turks traveling to Europe; on 1 July opening of new policy areas (chapters) in the negotiations on Turkey’s EU membership.

After half an hour Merkel and Rutte come out. A joint delegation meeting of Germany and the Netherlands follows. Merkel and Rutte sit on one side of the table, officials on the opposite. The official language is English. Merkel takes the floor first and talks about a breakthrough. She is, albeit cautious, enthusiastic. Rutte – jacket off – calls the Turkish proposal a surprise and a turning point.

Some officials are perplexed, react in disbelief, searching for the viper in the grass. But often there is none. Davutoglu waits and so Merkel and Rutte work through the text point by point. Virtually all the criticism erupting on the proposal in the days after is already on the agenda: Are the rights of refugees guaranteed? Where does the money come from? Where does it go? What happens to the conditions for abolishing the visa requirements? What “additional chapters” can be opened without political damage?

A Dutch official sends a text message to a colleague in the European Commission: “Are you still awake? Need your help.” The Commission person is already sleeping. When he reads the message the next morning, he immediately knows what it is about. “The cake was there, even the icing, what comes now is a beautiful cherry.”

Around midnight, a Turkish official pokes his head around the corner: how long will the delegation’s consultation last? Fifteen minutes later, Rutte and Merkel join Davutoglu, a bit later the officials come. For hours the Turkish proposal is negotiated. Rights, money, visas – it’s pushing and pulling. At half past two Davutoglu has food brought in: Turkish pizza.

At 3 o’clock Davutoglu thinks it is enough. “The problems are obvious,” he says. “Let our advisors now continue.” He, Merkel and Rutte leave for their hotel. Led by the Dutch top official Jan Willem Beaujean – permanent member of the Ankara club – consultants bicker until five hours later. The Turkish delegation is trying to cram in new demands. Beaujean cuts it off: “That was not what our bosses agreed upon.”

Afterwards de Gooijer sends a text message to Piotr Serafin, cabinet chief of Tusk: “It looks different. Meeting as soon as possible!”

Monday morning, 7 March. It is early day for the Dutch and German delegations. They realize that the news about a new deal will strike as a bomb. Not only because it is far reaching and controversial, but because 26 other heads of government, Tusk and Juncker did not expect this at all. “They had an invitation to a different party”, says a diplomat.

Around 8 am de Gooijer and Beaujean walk to the Justus Lipsius building for consultation with Serafin, Martin Selmayr (the right hand of Juncker) and two senior officials from the European civil service. “It was a how-do-I-tell-it-to-my-mother talk,” said one of those present. The two officials sniff: their carefully constructed “choreography” for the summit lies in ruins. Serafin is silent. He thinks about his boss who knows nothing and soon has the EU summit to lead. He also thinks of the unprecedented opportunities that are on the table. Selmayr listens carefully and then uses the word “game changer”. It is the Commission’s message that day.

It is 9 pm when Merkel and Rutte sit around the table with Tusk and Juncker. They explain the plan. Rutte praises “Donald” for his outstanding work. “Without your efforts, this would not have been possible.” Tusk speaks of a “disruptive, very uncomfortable proposal that is too promising to ignore”. Juncker hesitates, especially on the enforceability.

What follows is “Code Red,” as one official puts it: to do everything so that the frustration and annoyance of the now arriving – and waiting – leaders is restricted to a minimum. Merkel rushes to French President Francois Hollande. Rutte takes care of the Greek and Cypriot prime ministers, key players in the refugee settlement.

As expected, a storm of criticism rages over Merkel and Rutte. Their colleagues speak of a “robbery” and “sell-out”, warn against millions of visa-free Turkish tourists and against Turks in general (the Bulgarian Prime Minister: Never trust a Turk). Rutte and Merkel listen and explain, but also ask their colleagues: What is your alternative?

Diederik Samsom is in Brussels that day, for consultations with his Socialist colleagues. He smiles broadly: the ball is rolling in the direction desired by him. In the afternoon the Dutch delegation is bursting into the Justus Lipsius building: Rutte is there, Merkel, Hollande, David Cameron, Alexis Tsipras, EU Foreign chief Federica Mogherini and Cypriot President Nikos Anastasiades. The Cypriot vetoes the Turkish demand to open five “enlargement chapters” that Cyprus had frozen earlier. Dutch-German pressure leads nowhere. Anastasiades knows he can never come home if he says yes. It would be the destruction of the promising talks on reunification for his island – the opportunity of this century. “The unity of Cyprus is above that of the EU”, the Cypriots lets us know.

Only in the evening does Davutoglu join. He negotiates for hours with Merkel, Rutte, Tusk and Juncker on a new text, the basis for an agreement. The tension sometimes runs high, Juncker and Tusk smoking. Davutoglu complains that EU leaders delay their promised billions. Again it is late, again there is pizza, Italian this time.

Around one o’clock in the morning there is a compromise outlined; a total agreement was not possible yet. The billions for Turkey come later, the visa freedom shifts from early to late June, the rights of refugees are not yet insured, but the core of the proposal launched Sunday night remains: Turkey takes back all migrants. In ten days, in accordance with the deadlines set by Tusk and Rutte, the agreement must be signed.

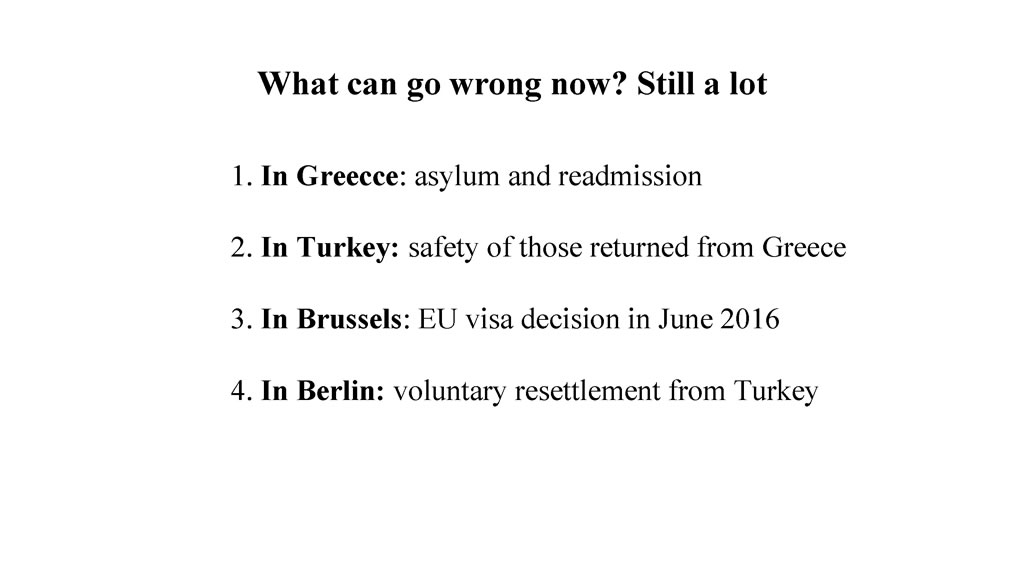

“We now have a week to save the reunification of Cyprus and to rewrite the Geneva Convention,” an EU official notes cynically. Tusk takes over the lead from Merkel and Rutte and travels to Nicosia on Tuesday, 15 March. He assures Anastasiades that his island will not be sacrificed on a Turkish chopping block. “Cyprus is not for sale,” Tusk announces indoors. In his pocket he has a solution to the controversial five chapters demanded by Ankara. Turkey gets another chapter, number 33, which deals with how Turkey – if it ever becomes a member of the EU – should contribute financially to the Union. “A completely empty gesture,” said an EU official.

Then Tusk flies to Ankara. After his meeting with Davutoglu, Tusk says that there is still a lot of work to be done.

At midday on Thursday, 17 March, the EU leaders arrive in Brussels for their spring summit. During dinner they give Tusk and Rutte a mandate to negotiate with Davutoglu the next day. Hard conditions: hands off Cyprus; no cheating with the visa requirements; no infringement on the rights of refugees. Before the meeting closes, Tusk calls on all leaders to cancel any separate agreements with Davutoglu. He does not feel like new surprises.

In the morning of Friday, 18 March, Tusk, Juncker, Rutte and Davutoglu sit around the table once again. During the first round of talks, the Turkish Prime Minister puts everything up for discussion; his interlocutors are afraid of a new night-time summit. Panicked tweets continue to appear on Saturday. But from the second round it goes in a straight line towards the agreement. Tension hardly arises. The only hassle arises when Davutoglu pulls at the Belgian authorities that allow PKK supporters to demonstrate in Brussels.

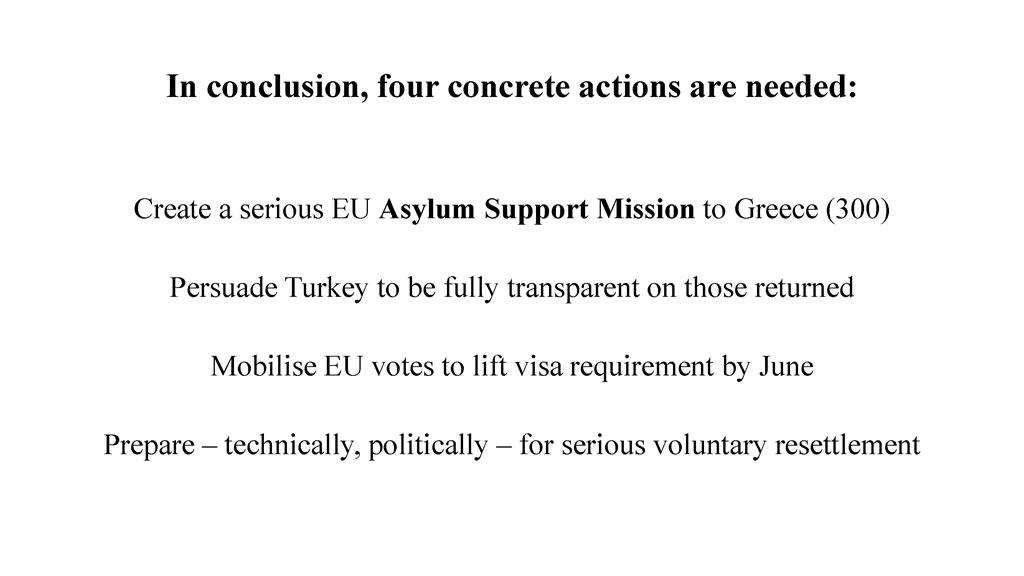

A little before five in the afternoon Tusk tweets: “Unanimous support for the EU-Turkey deal.” The hook, which Rutte on 17 December nailed to the wall, supports the agreement; Turkey takes the migrants back, may close borders, must guard borders. The turnaround in asylum policy is a fact. “This was the easiest part of the deal,” an EU official notes blithely. “Now comes the execution.”

Marc Peeperkorn