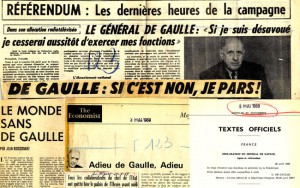

In his wonderful book on Turkish history – The Young Turk Legacy And Nation Building – Dutch historian Eric J Zuercher has an intriguing chapter on “Turning Points and Missed Opportunitities in the Modern History of Turkey: Where Could Things Have Gone Differently?”. Here he discusses how Ottoman and later Turkey history might have developed if the wars of 1877 and 1912 had NOT taken place; if there had NOT been the Istanbul uprising of April 1909; if Kemal Ataturk had NOT established “an almost totalitarian grip” over the country in the 1920s; and if the transition to democracy after World War II had happened differently. And Zuercher concludes:

“it is a very useful exercise for us historians to remind ourselves that the historical developments with which we are all too familiar, should not be seen as inevitable … Thinking about what could have been makes us more sensitive to processes and contingencies that we too easily overlook when we already know how the story ends.”

It is indeed a useful exercise and I only regret that Zuercher stops his what if in the 1950s.

One of the most intriguing missed opportunities in Turkey’s modern history surely took place in the late 1970s, when Turkey decided not to follow Greece, Spain and Portugal and did not submit an application for full EU accession. Why did it not? Would it have succeeded? Was it discouraged by EU member states or was this above all a result of its internal politics?

I have long been puzzled by this question; and so far I have found it difficult to find detailed accounts of what actually happened then. For now I only hope that Zuercher, or some other curious historian, will go and look in the diplomatic archives to tell us the full and real story.

Here are, for now, the outlines of this missed opportunity as I have pieced them together from different sources.

On 12 June 1975 Greece, having just emerged from military rule, submitted its application to the (then) European Economic Community (EEC). Negotiations started in July 1976. On 28 March 1977 Spain submitted its application. This was followed by Portugal in July that same year.

If Turkey had submitted an application at the time chances are that it would have been very difficult for the EEC to reject it while accepting Greece. While some EEC countries (including, not surprisingly, the France led by president Valery Giscard d’Estaing) did not believe that a Greek and Turkish application would necessarily be treated together, others apparently disagreed. Armagan Emre Cakir discusses evidence that some high level European politicians and officials travelled to Ankara and urged the government of the prime minister Bulent Ecevit in 1978 to apply. Ecevit was opposed; so was his deputy prime minister at the time, the Islamist Necemettin Erbakan. It seems that for Ecevit the EU was too capitalist; for Erbakan it was too much a “Christian club.”

There were even then those in Turkey who urged the country to be more proactive. The Turkish ambassador in Brussels, Tevfik Saracoglu, returned to Ankara in summer 1975 (after Greece had just applied) urging the prime minister Demirel, and party leaders Turkes and Erbakan to do the same. He left empty handed.

In May 1978, as the membership for Greece was finalized, Ecevit, instead of submitting a Turkish application, froze relations with the EEC.

But this was not the last chance. In 1980 the foreign minister of Turkey, Hayrettin Erkmen, told the government of Suleyman Demirel that Turkey should apply urgently. Erkmen failed. In fact, in July 1980 the Islamist Erbakan brought a motion against him into the parliament because of his idea to take Turkey into the EEC. This motion was supported by the left-wing Kemalist Bulent Ecevit. And so Erkmen was removed from office on 5 September 1980.

A week later, on 12 September, tanks rolled in streets of Ankara and Istanbul, as a military junta took control of the country. One of Turkey’s darkest periods was about to begin.

This is the rough outline of what must surely be regarded as one of the great missed opportunities of modern European history. I wonder if a Turkey on route to joining the EEC would have experienced the brutal coup in 1980 that finally and decisively separated its fate from that of other European Mediterranean countries with autocratic traditions. Greece joined the EU in 1981. Spain and Portugal followed in 1986. In 1989 the Berlin Wall came down and the division of Europe ended. During this time Turkey first adopted a military-inspired constitution, then fought a bitter counterinsurgency campaign against the PKK – while trying in vain to suppress all expressions of a separate Kurdish identity. Economically the gap between Turkey on the one hand and Spain, Portugal and Greece on the other became ever wider during the two decades that followed.

I hope this fascinating episode will one day soon be researched in depth. Unfortunately Hayretting Erkmen died in 1999, so it is no longer possible to interview him. Erbakan also died, as did Ecevit. And yet, there must be witnesses and documents that would allow a diligent historian to reconstruct the events that led to such a tragic denouement.

This also qualifies a claim sometimes still made by Turkish politicians that the EU has prevented them from joining the EU “for half a century”. For much of that period it appears Turkey’s biggest obstacle were the attitudes of Turkey’s leaders.

One also hopes that Turkey’s leaders do not repeat the mistakes of this time and miss further windows of opportunities. I could think of a few even now. This is, however, another story.

PS: If any readers know of any more detailed study of this period, in English , German or Turkish, please let me know at g.knaus@esiweb.org!

Moderating a one day brainstorming on the future of the Albanian economy in Tirana, August 2013 with next Minister of Labor and welfare, Erion Veliaj, incoming prime minister Edi Rama and the next minister of Finance, Shkëlqim Cani

Moderating a one day brainstorming on the future of the Albanian economy in Tirana, August 2013 with next Minister of Labor and welfare, Erion Veliaj, incoming prime minister Edi Rama and the next minister of Finance, Shkëlqim Cani

![IMG_4336[1]](https://www.esiweb.org/rumeliobserver/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/IMG_43361-300x225.jpg)