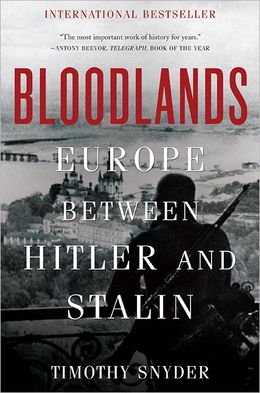

Rashadat Akhundov, NIDA activist, sentenced to eight years in jail in May 2014 with seven other activists.

A graduate of the Central European University in Budapest.

This morning Azerbaijan’s most courageous investigative journalist, Khadija Ismayilova, published (unfortunately expected) bad news from Baku: the verdict in the case against NIDA youth activists in Azerbaijan:

“Verdict is announced. Democracy activists from Nida! Civic Union are sentenced for exercising their right of freedom of assembly:

Rashadat Akhundov = 8 years

Zaur Gurbanli = 8 years

Ilkin Rustemzade = 8 years

Bakhtiyar Guliyev = 7 years

Mammad Azizov = 7.5 years

Rashad Hasanov = 7.5 years

Uzeyir Mammadli = 7 years

Shahin Novruzlu = 6 years”

This verdict comes on the eve of the visit to Azerbaijan by the secretary general of the Council of Europe, Thorbjorn Jagland, and almost exactly one week before Azerbaijan takes over the chairmanship of the Council of Europe.

ESI has written a lot on this issue recently – and I have written on it here a few days ago. We will publish more in the coming weeks.

On this sad day for human rights in Europe – on this truly shameful day for the Council of Europe and its member states, who have failed dissidents and human rights defenders in Azerbaijan – the best is to let the NIDA activists speak for themselves. Here is the speech they delivered in court on 5 May. These voices will not be silenced:

Bakhtiyar Guliyev, Shahin Novruzlu, Mahammad Azizov, Reshad Hasanov, Rashadat Akhundov, Uzeyir Mammadli, Zaur Gurbanli, İlkin Rustemzade

Date: 01/05/2014

To the Baku Court on Grave Crimes

Dear Court,

Dear trial participants,

We, as defendants, have decided to represent ourselves as one person for our last speech to the court. The reason for this is that the government does not see us as individuals, but rather targets the NIDA civil movement that we are members of and subjects it to repression. You may consider our last plea as coming both from the eight NIDA activists present here and other NIDA activists who are either free or under arrest.

Usually, defendants ask for mercy from the court, and sometimes express their regret. We don’t need mercy, nor do we feel regretful, since we have not done anything to regret. Nor do we expect justice from the court that is hearing this fabricated lawsuit, as it is not capable of maintaining the sanctity of the law and making independent and just decisions. The hollowness and meaninglessness of this lawsuit have been unconditionally proven by the truths we have told, the statements made by witnesses, as well as other evidence presented by the defense in their high quality speeches.

The start of the smear campaign against NIDA was made obvious during the first days of the arrests – when Mammad Azizov, Bakhtiyar Guliyev and Shahin Novruzlu were forced to sign completely slanderous texts, memorize them and then recite them in front of cameras after being subjected to physical violence and torture. During this, TV channels continuously disseminated videos provided to them by the Interior Ministry, and government spokespeople and members of parliament made statements implying NIDA aims to create chaos in society.

Ilham Aliyev, president of Azerbaijan since 2003.

There was no doubt that these repressions were politically motivated after President Ilham Aliyev named us as criminals during the YAP (New Azerbaijan Party) assembly on June 7, 2013, when investigations were still ongoing and no valid court verdict had been issued. This statement was the decision that sealed our fate. This decision framed the judicial investigation.

Under such circumstances, we are aware of the fact that neither the state prosecutor, nor you, the judges, have any other options to pursue. Your responsibilities in the court are limited to acting as notaries to legitimize this politically motivated order. Even if the law and your conscience demand you to act otherwise, you shall not dare stray from this order. We should also mention that we are not the sole victims of the regime in this trial. Your appointment as the judge and the prosecutor also makes you victims of this fabricated court case. Indeed, we – behind bars and you – at liberty are all hostages and victims in this big prison called Azerbaijan.

That’s why it is difficult to demand anything from you. How can one prisoner help another one?

We do not intend to go deeply through all the details of the case. Because it’s already obvious that even as a pseudo case they could not manage to organize it more maturely and systematically. Nevertheless, we will go through several issues.

The prosecution claims we were arrested due to a protest on March 10. This is partly true.

Why partly and why true? And why shouldn’t we regret this?

Let’s begin from the very first question. As to the prosecution’s testimony, they imprisoned us due to our social activity and particularly for our activity within the NIDA civic movement. But it was not because of events on March 10. NIDA managed to involve mature and active youth in its membership. At the time we hadn’t announced that we were totally opposed to the government. Meanwhile, the government was already against us. Because this regime is an enemy to all active and valuable people who want to spoil its plans for society to remain passive, villainous, obedient and enslaved. Thus, the government is a direct foe to the youth who are indicators of activism, dynamism and who are against slavery. As we see, the government doesn’t chase us because we are criminals. On the contrary, if we committed a crime, we would be friends of this regime. Because they themselves are of a criminal nature. Thus, they arrested us not only because we protested the death of our brothers on March 10, but also because of our nonviolent struggle, which is not forbidden by law.

If there is any sign of a tendency for violence, solely the government is responsible for it. As the government creates unlawful conditions, people become more aggressive and want revenge. Of course, it encourages a bias towards violence. Being a civic movement, we did our best to prevent physical confrontation and propagate nonviolent struggle. We used numerous examples from global experience that prove that nonviolent struggle is far better than violence. Ironically however, we were accused of violence. Our criminal case took its place at the top of the list of ridiculous crimes in the world.

And shall we regret it?!

We are arrested for and proud of demanding freedom, rule of law, and human rights for the nation we belong to, for the land we are residents of.

Everyone has clearly seen the torture and abasement that the first three arrested activists have encountered. But unfortunately, the court didn’t even attempt to investigate the case. The court process is enough to eliminate these testimonies from the list of evidence. But of course only an independent and fair court could precisely evaluate and take the necessary course in this way, not you!

NIDA trial

Observers [of this trial] probably remember the testimony of Anar Abbasov, the main witness of the prosecution, whose addiction to drugs and mental problems was evident even without a professional examination. His testimony became an exercise in contradiction. He couldn’t describe the Venice café [where according to the indictment, he witnessed the activists’ discussion of their plan for violent action], he didn’t even know what NIDA! (exclamation) means, he couldn’t recognize the people, whom, according to the indictment, he identified as participants of the violence-planning meeting, he couldn’t remember anyone’s name, his testimony was a bunch of nonsensical words about NIDA and Venice. That witness was in fact the best proof of our innocence.

The government accuses us of cooperation with foreign groups. Just imagine, the accusation of using violence comes from the government, which came to power via a military coup, which used arms for violence against its own people including the events of October 15-16, 2003, the assassinations of dozens of the best thinkers, like Elmar Huseynov, Ziya Bunyadov, Rafik Tagi. It comes from the government that has its own people’s blood on its hands. And yes, it is the irony of history.

Unlike the YAP members who would trade away Azerbaijan’s interests to foreign countries, who would do anything in order to maintain the dominance of the ruling party, we NIDA activists have never been slaves of the Russian KGB, nor have we worshipped the U.S. or European oil magnates’ money, nor followed the Iranian mullah’s and Turkish Nurchu’s ways. NIDA activists are patriots ready to sacrifice their youth and lives for the sake of the nation without the slightest hesitation. The charges imposed on us are simply the government projecting its ugly nature onto us.

Having touched upon the foreign affairs issues, we would like to share our opinion on the case of the Ministry of National Security stealing AZN 94,000 from Shahin Novruzlu’s father and calling it a crime. There was enough evidence provided by the witnesses at the hearing to prove that this money belonged to Shahin’s family. We can compare this to another incident. 12 September 1980, the junta that came to power by military coup in Turkey, staying loyal to their methods, executed 17-year-old Erdal Eren. A great republic with 100 years of history like Turkey still is not able to clean the stain called Erdal Eren. After 33 years, in Azerbaijan Erdal’s peer Shahin is being accused by YAP, and loyal to their values they stole Shahin’s father’s money. The military men do what they are used to – murder, YAP members do what they are used to do – theft.

While governments are transitory, be sure of the fact that Shahin’s arrest and the theft of his family’s, in particular his aunt’s hard-earned money will hang over Azerbaijan’s shoulders like the Sword of Damocles, and we as a nation and a country in general will always be ashamed of it.

Two of us have been charged with hooliganism because of a simple dance. However, this dance doesn’t have any signs of hooliganism, not to mention any criminal implications. The evidence provided and the defense speeches have proven this. Therefore, in our final speech we would rather talk about the main reason for the arrests than the legal aspects. The objective of introducing this article to our case is to present us as “immoral” to society. This is precisely why the host of the disgraceful Lider TV, who has previously presented pornographic scenes shot by secret cameras, now misinformed the public by making fun of our alleged participation in the dance (deliberately misrepresenting the facts as if the eight people sitting here are in fact the eight people who are seen in the Harlem Shake video). However, despite their cheap and meaningless efforts, the dance cannot be considered as immoral. Immorality is to steal or sell parliamentary seats, falsify elections, be an oligarch or rip off the nation of its last piece of bread. The fight against this immorality is the most honourable, glorious and moral job to do.

Our court case, with each of its details, has discredited the government and shown its real face. Please pay closer attention to the above-mentioned witness, Anar Abbasov. He is a bright example of the zombie population that Aliyev’s regime has been trying to bring up for the last 21 years. This “new Azerbaijani” is meant to be cowardly and sinful, his morality must be tainted with slavery and sycophancy, he should be able to slander even his own brother when the time comes, he should be corrupt enough not to dare to stand against even a slight injustice with a life credo of adulation of the authorities and hypocrisy. In the past 21 years, the ruling party was considerably successful with their mission of creating this “new breed of Azerbaijanis”.

Solshenitsyn (in Soviet prison)

Solshenitsyn in his “Live Not By Lies” wrote about despotic regimes’ dependence on everyone’s participation in the lies. He wrote that the simplest and most accessible key to our self-neglected liberation lies right here: Personal non-participation in lies. This is what NIDA does.

The NIDA civic movement tried to resist and prevent a complete victory of this government’s policy. Our and other members’ ongoing arrests, openly demonstrated anger and irritation we came across prove that we are on the right track to hamper this policy. Our determined resistance, persistent position and speaking the truth (despite the benefits of the government’s side) couldn’t have been achieved in any other way.

There is something they do not realize. If there is an evil happening in one place, even if everyone turns their faces away, those who are humane have to face it. We as free men cannot turn a blind eye to evil, immorality, and in general the government’s misdeeds; we will only bow in front of a righteous power. The ideology of the Republic sees it as evil to live under someone else’s despotic regime (will), because slavery creates the worst of its consequences- a state of vagrancy and sycophancy. We as true republicans, despite the dangers, will not trade freedom for the comforts of slave lives!

Therefore, the regime’s police and other power structures’ violent and brutal actions disguised as “service to law”, presenting our constitutional right of freely gathering as a riot, calling our peaceful struggle a violent act, and our fabricated arrests do not scare us and will not make us back away from our position. The clarity of our fundamental principles, and our loyalty to them, our complete rejection of radicalism, immorality and violence are the reasons why hundreds of people with a similar ideology joined our cause in the course of the past year.

As mentioned earlier, our participation in this court is a mere formality. Our plea to be acquitted from these falsified criminal charges is also a formality. But we are confident that acquittal will come not from the court but from our people and history. There is another reason for coming to the court and giving this “final speech”. We value the court system as a foundation of the state and guarantor of social justice. We respect and honour the splendour carried in the word – court. Therefore, despite the fact that the standards of this court falls far below these criteria, out of respect to the judge and the court we are obeying the formal procedures and continue to strive to do so.

Sahin Novruzlu, the youngest activist, was 17 at the time of his arrest

The final word has yet to be uttered. The final word will sooner or later come from the nation that stands for the arrested ten [meaning the eight NIDA activists in this case and Abdul Abilov and Omar Mammadov – two Facebook prisoners facing trumped-up drug charges] NIDA activists, and our counterparts.

The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates was brought to court under the accusation that he was poisoning the thoughts of youths. He could have left the country or accepted to stay silent, to not spread his ideas. Otherwise, he knew that he would be executed. At the trial, Socrates declared that he would not sacrifice the truth for his freedom and life, and chose death. We will also not sell the truth for anything – whether we’re free or jailed.

We are not alone. Our determined intellectuals and public figures – the Chairman of “REAL” Ilgar Mammadov, Deputy Chairman of “Musavat” Tofig Yagublu, Yadigar Sadigov, Gurban Mammadov, Anar Mammadli, main representative of the believers in Azerbaijan, Taleh Baghirzade, our falsely accused young friends Ebdul Ebilov, Omar Mammadov, Elsever Murselli, Rashad Ramazanli, journalists Rauf Mirgadirov, Perviz Heshimli and dozens of other prisoners of conscience and political prisoners, are kept in jail under false pretences, specifically for telling the truth. This government has to understand that, even if there is only one person in the country with a conscience, he will continue the resistance against their atrocious anti-people politics. Finally, the truth will triumph over lies.

Even though we have reached a level of corruption that has no parallels, we know that the exams for the selection of the judges and prosecutors for our cases are challenging. Because of that, our judges and prosecutors, usually, have to possess some knowledge of law. We do not doubt that the current panel of judges and the public prosecutor in front of us also possess a high degree of legal literacy. This is also evident from the fact that Azerbaijan’s strongest lawyers are defending us and you have specifically been chosen to go against them, the political order of making a case for these absurd allegations has been given specifically to you.

The ultimate aim of the law is to provide justice. You, also, possess the qualifications to professionally determine justice. It is impossible for you not to see that these allegations are frivolous and this, we are sure, you do not doubt. Because of that, it will be very hard for you to give us our sentence. Because the trial of conscience that comes forward from the honour of one’s profession and humanity is harder than the trial of this sort. Despite this, comfort will conquer conscience and you will read out our conviction. For this reason, we do not ask anything from you. Quite the opposite, in order to calm your conscience, to give you comfort, we are letting you know that the years that are being taken from our lives with your sentencing are not going to waste. It is a capital investment in the freedom of Azerbaijan. So, even though you may be an anti-hero, you are also doing something for this country.

We took into consideration that we are a capital investment in freedom when we started this journey. Now, can we be sorry for the accusations, for the thoughts and actions which we did not commit?!

We declare once again that we are confident and you should be confident, that because of our desire for freedom for this nation of which we are part of, this region in which we are residing, because freedom, democracy, rule of law are of the highest value and the rights and freedoms of the citizens of this country should be respected, because of our efforts in this sphere we have been arrested and of this we are proud.

We ask our friends, peers, and specifically our parents to be ready for a heavy sentence and not to give way to hysteria, damnation, or insults. Everyone aside from the foreigners are victims in this courtroom and it is inconsequential and meaningless for a victim to curse out another victim.

We say thank you to everyone who took part in defending us, including those who share our beliefs, to our family that is always with us, to little Araz, to our lawyers who selflessly defended us. We express our gratitude to the local and international human rights organizations, parties, and other organizations, foreign states and their embassies working towards restoring our rights. We are grateful to the representatives of foreign embassies and international organizations who have participated in our trial for half a year, because they have also proven that the Western values which we have been defending are not based on oil, or geostrategic material interest, but on freedom and justice.

Lastly, from here we want to reach out to the NIDA fighters outside. During Soviet times, a seven-member organization called “Ildirim” [“Thunder”], of which all seven members were jailed for their anti-Soviet efforts, Ismikhan Rahimov-a member turned to his relatives after his sentence was read, while being placed in a vehicle and said: “We are leaving, but we will be back.”

Now, we are delivering to you the words of Sir Ismakhan in another form: We are not going anywhere and coming back. Because we exist anyway, we are here, with you. Even if ten members of NIDA are in jail, those of you who are free are replacing us. We call on you to continue the fight for us with even more principal and relentlessness. Do not ever surrender to slander! Hold your heads high, your wills strong!

Down with dictatorship and despotism!

Long live the people who do not bow to oppression and injustice!

Rashadat Akhundov

Rashad Hasanov

Uzeyir Mammadli

Zaur Gurbanli

Ilkin Rustamzade

Bakhtiyar Guliyev

Shahin Novruzlu

Mammad Azizov

The Palace of Europe in Strasbourg

The Palace of Europe in Strasbourg Council of Europe

Council of Europe